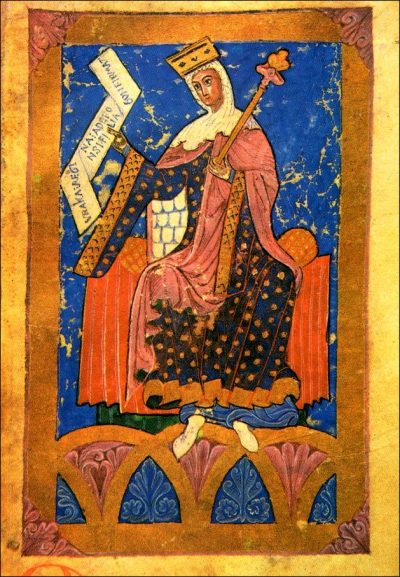

Queen Urraca, as she appears in Tumbo A Cartulary of the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela, ca. 12th c.

Dani Carson, an honors biology major with minors in English and Medieval and Renaissance studies, participated in her second Honors Passport course and was awarded a particularly juicy topic to research and present to the classmates who joined her on the Camino de Santiago. She stumbled upon family intrigues, power grabs, a murder and the Holy Grail while researching the Church of St. Isidore in León, Spain. Read on to learn how the royal abbess Urraca eliminated the competition and masterfully manipulated 11th-century propaganda.

In Medieval France, the patriarchy reigned. However, once we crossed the Pyrenees through the Somport pass into Spain, we found that women dominated many areas. These women ruled their small kingdoms, only requiring men for their signatures to carry out their wishes. They could gain the most power if they held positions of secular royalty and religious prowess. A royal abbess held the most power a woman could attain in Spain. She controlled both secular and religious affairs, deciding upon taxes, facilitating agreements between regions and in local politics, and more.

Queen Urraca of Zamora (ca. 1033-1101) is one such abbess. She was the eldest daughter of Queen Sancha and King Ferdinand I and had three siblings: Alfonso VI, Elvira, and Garcia. She also had a step-sibling named Sancho whose mother was a Moorish princess named Zaida. When King Ferdinand I died in 1065, he gave each of his children an infanta, or a “kingdom within a kingdom.” A murderous family drama ensued.

Sancho, who Urraca and Alfonso VI considered illegitimate because of his mother, began taking over his siblings’ infantas. He overtook Garcia and Elvira with ease. However, in another battle, when trying to escape, Sancho was killed. Alfonso VI and Urraca were rumored to have organized his assassination in order to keep their own kingdoms under their own control.

Urruca consolidated her power through propaganda, focusing on the Basilica of San Isidoro. This church was built on top of a Roman temple, then became a monastery dedicated to Saint John the Baptist, and was re-dedicated to Saint Isidore when King Ferdinand moved his relics from Seville to Leon in 1063. St. Isidore’s relics put Leon on the route of the Camino de Santiago, though it did not become a popular pilgrimage site until Urraca inherited the church upon her father’s death.

Once Urraca obtained this church, she used it to bolster her own power over the area. She gave the church many gifts, included a chalice made of onyx which she had overlaid with gold and jewels. This chalice originates from the first century and is rumored to be the Holy Grail. She was also the patron of the paintings that decorate the Pantheon, or royal burial chamber, connected to the church of Saint Isidore. These paintings feature Christ’s life, yet the image of Christ on the crucifix includes figures of Queen Sancha and King Ferdinand I kneeling beneath the cross. There also used to be an image of Urraca herself at the base of the cross, also kneeling, which was probably covered during renovations or deteriorated over time.

Urraca also used her name and title to brand the gifts she made. The chalice is engraved in gold, stating that Urraca, Queen of Zamora and daughter of King Ferdinand and Queen Sancha, gave this chalice to Saint Isidore. Whenever she made decrees or speeches to fellow religious members or lay people, she would always begin with introducing herself as “Queen of Zamora by decree of King Ferdinand.” Also, the image of her kneeling in the paintings of the Pantheon include an inscription that read “Mercy. Urraca daughter of King Ferdinand and Queen Sancha.” All of this name-dropping served to reaffirm her power and rightful place as royal abbess of the area.

Portal at the Basilica of San Isidoro, León, showing the sacrifice of Isaac. This Old Testament scene was an unusual choice and was likely deployed for political purposes by Queen Urraca.

Urraca also used the portal of the church itself to remind the people of her position, as well as to discredit the illegitimate branch of her family, and by extension, the Moors. As Christians would pass into the church of Saint Isidore, they would walk beneath a tympanum (a decorative, semi-circular piece above a portal) that showed reliefs of the sacrifice of Isaac. Usually, a tympanum of this time period would contain images of Christ. However, in this tympanum imagery, Isaac moves from the right side. He rides to the mountain, takes off his shoes as he steps onto holy ground, and then is held by Abraham with a knife to his throat. From the left, Ishmael points an arrow toward the symbol of the Holy Spirit, a lamb, as he rides a donkey away. Hagar, Ismael’s mother and second wife of Abraham, lifts her robes to show her thigh—a sign of lustfulness and sin. Continuing toward the center, an angel holds a ram to Abraham, who stands holding the knife as the hand of God reaches down from above to him.

This is a fairly usual Biblical scene, except that the capitals that crown the pillars below the tympanum show demon-like women squatting. They represent Hagar, and thereby Zaida and the Moors; Hagar is made into a sinful woman, which she was not considered to be in the Bible. Historians believe that Urraca chose this tympanum in order to draw parallels to her own family in this scene. King Ferdinand would be Abraham, the patriarch, while Zaida would be Hagar, the second wife. Alfonso VI would be Isaac, the rightful heir. Sancho would be Ishmael, the illegitimate son. In this scene, therefore, Urraca demonizes Hagar to portray her anti-Moor sentiments. She would also show that she and her brother, Alfonso VI can win with God over both Sancho and the Moors. Urraca created power plays throughout the church and Patheon at the church of Saint Isidore, and this ensured her continued power as royal abbess of Zamora.