By Laurent Bellaiche

Several famous people have provided interesting quotes about destiny. For instance, William Shakespeare said, “It is not in the stars to hold our destiny but in ourselves,’’ while Winston Churchill indicated, “It is a mistake to look too far ahead. Only one link of the chain of destiny can be handled at a time.’’ Similarly, some deep thoughts have been given to the concept or fate. This includes Heraclitus stating, “A man’s character is his fate’’ or Napoleon Bonaparte declaring, “there is no such thing as accident; it is fate misnamed.’’

The question for today’s assignment is which quote about destiny or fate relates the most to the stories below, which all happened on the biggest stage on Earth: the FIFA World Cup.

The first World Cup occurred in 1930 and was hosted by Uruguay. One favorite was Argentina who had won the Copa America just the year before and obtained the silver medal at the 1928 Olympic Games. A forward from the club Huracan, Guillermo Stábile, was selected for the first time with this South American country to take part of this World Cup. He did not play the first game that Argentina won against France 1-0 with difficulty thanks to a goal scored nine minutes before the end by the tough Luis Monti, who had previously injured a French player, Lucien Laurent. Stábile was called for the second match against Mexico, though, and had a tally of three goals for a 6-3 win during his first game with the country of los Gauchos. His spectacular form remained during the next match with their neighbor Chile, with two goals that greatly contributed to the 3-1 victory. Stábile then put again the ball at the back of the net twice during the semi-final, where Argentina crushed the United States 6-1. It was now time to face another neighbor in the final, the great Uruguayan team that was the double reigning Olympic Champions of 1924 and 1928. Uruguay triumphed 4-2, despite another goal from Stábile. He had made the net shake eight times in only four games and was the top scorer in the first World Cup. Shockingly, these four games were the only ones Stábile ever played for Argentina since he was never called again for his national team after 1930. He rather pursued a career in Europe, with the Italian clubs of Genoa and Napoli and the French team Red Star Paris.

Another great striker, Just Fontaine, was also the unexpected hero of another World Cup in 1958. France had qualified in part due to a fantastic forward named Thadée Cisowski, who had a tally of two against Iceland in 1957 and had tied in 1956 and against Belgium for the highest number of goals during a single game (five) with France. Unfortunately, Cisowski was prone to injury and could not participate to the 1958 World Cup in Sweden. The French coaches had to decide between Just Fontaine and another efficient scorer, René Bliar, for the center-forward position. Surprisingly, both players were separately told they were the first choice, but Bliard suffered an ankle sprain during a training session. Fontaine took full benefits of his destiny or fate with three goals against Paraguay for a 7-3 win, the two French goals during the 3-2 defeat by Yugoslavia and another goal against Scotland, all in the group stage. During the knockout stage, he was again on the scoring sheet, twice against North Ireland for the 4-0 win in the quarterfinal, and once when France lost to the future winner, Brazil, by 5-2 in the semifinal. Before the last game for the third place of this World Cup opposing les Bleus to West Germany, Fontaine had thus already scored nine times. Many wondered if he could approach, tie, or even break the record of 11 goals accomplished by the Hungarian Sandór Kocsis during the previous World Cup of 1954. Fontaine put the ball at the back of the net four times during that game, including two during the last 12 minutes. Just Fontaine had therefore scored the staggering number of 13 goals in a single World Cup, a record that will probably never be beaten. Not bad for someone who should not have been the starting center-forward!

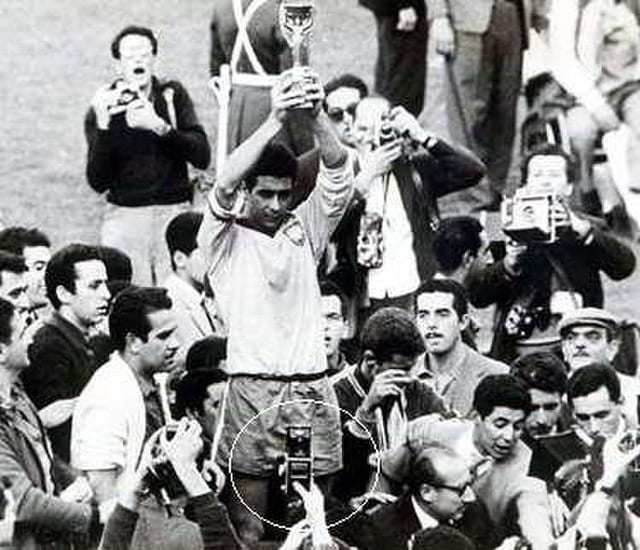

Four years later, Brazil went to Chile in the hope of retaining their world championship. Their number 10 was a 21-year-old Pelé, who was already the best player in the world. His first game against Mexico was simply brilliant with one assist for Zagallo and one goal after having dribbled four defenders. However, when facing Czechoslovakia during the second match for a 0-0 draw, he tore a thigh muscle and was ruled out of the entire world cup! How was Brazil going to respond to such a tragedy? The answer is quite simple. They relied on substituting Pelé with Amarildo, Garrincha and Vavá, who stepped up their games. Brazil won 2-1 the next game against Spain, thanks to two tallies of Amarildo; then eliminated England 3-1 in the quarter-final with two goals of Garrincha and one of Vavá, before preventing the home country of Chile from reaching the final by winning 4-2, with all the Brazilian goals being made again by Garrincha and Vavá (who found the net twice each). Brazil met Czechoslovakia again in the final. Masopust, who will be elected a few months later the 1962 Golden Ball winner, put the Eastern European team ahead after 15 minutes, but Amarildo equalized two minutes later. Zito and then Vavá added two more unities. Brazil succeeded to be world champions again after 1958, thanks to three goals from someone who should not have played during that tournament (Amarildo) and four tallies each for two forwards (Garrincha and Vavá) who would have probably been in the shadow of Pelé. Garrincha and Vavá were even the top scorers of the 1962 world cup, with the Chilean Leonel Sánchez, and made history: Garrincha was the first person to have won the World Cup while being at the same time its top scorer and being elected its best player. Vavá was the first footballer to have scored in two different World Cup finals, that are 1958 and 1962 in his case.

Interestingly enough, the English captain during this Brazil-England match of 1962 was forward Johnny Haines, nicknamed the Maestro, who finished third in the 1961 Golden Ball competition and who is often considered as the greatest player in the history of Fulham. There was no doubt that after having also participated to the 1958 World Cup, he was going to lead the English team at the next world tournament held on home soil in 1966. However, Haines was injured in a car accident in August 1962, with broken bones and an injured knee, and never fully recovered. English coach Alf Ramsey then selected the great Jimmy Greaves from Tottenham and Roger Hunt from Liverpool, as well as the younger and less famous John Connelly from Manchester United, Terry Paine from Southampton and Geoff Hurst from West Ham as forwards for the 1966 World Cup. For the first game against Uruguay that ended in a 0-0 draw, the English line of forward was formed by Greaves-Hunt-Connelly, which then became Greaves-Hunt-Connelly for the 2-0 win against Mexico (with a goal of Hunt) and then only Greaves-Hunt for the 2-0 victory against France (with Hunt on the score sheet again, this time twice) since England decided to play with four midfielders and not anymore three from now on. Greaves got injured in that last game and Geoff Hurst took his spot in the quarterfinal, where he scored the only goal of the match against Argentina in a very tense match. Hurst and Hunt continued to be aligned for the semi-final, where England faced Portugal and won 2-1. England has thus reached the World Cup final for the first time against West Germany. Greaves has recovered from his injury and was fit to play. However, Ramsey decided to choose Hurst and Hunt in the frontline again, and guess what happened? Geoff Hurst scored the first hat-trick in a World Cup final and was thus instrumental in the 4-2 win of England! Hurst has thus taken his destiny in his own hands, for which he was knighted in 1998. Interestingly, one goal of Hurst during that final is still the subject of intense debate, since it is not for sure that the ball crossed the line after hitting the crossbar. It was in fact the Soviet linesman, Tofiq Bahramov, who indicated that the goal should be awarded. It is very likely that Bahmarov had a prejudice against Germans because of World War II. A myth even said that, when asked on his deathbed why he allowed the goal, he simply answered “Stalingrad’’.

Fast-forward to 1978 when another country won the World Cup at home for the first time in its history: Argentina. The coach, César Luis Menotti, had decided to create a commando spirit and to only select players from Argentinian clubs. However, he made two exceptions to that drastic rule by inviting the experienced 31-year-old defender Osvaldo Piazza from the French team Saint-Etienne and the much younger 23-year-old forward Mario Kempes from Valencia, Spain. Piazza declined the invitation officially stating that he wanted to stay close to his wife and children who were involved in a car accident in April 1978, while rumors indicated that he was opposed to Argentina’s brutal military dictatorship at that time. On the other hand, Kempes accepted to take part of the 1978 World Cup, where he won it, as well as finished top scorer (with 6 goals including two in final for a 3-1 win against the Netherlands) and was elected best player. 16 years after Garrincha, Kempes realized this incredible triple feat. Was it fate that incited Menotti to bend his rule to call Kempes? What is also rather incredible is that Kempes never scored again for Argentina after that 1978 World Cup while he still played for it until the 1982 World Cup. Does someone have to grasp destiny as soon as he/she can, because it only occurs within a short period of time?

Talking about 1982, another forward also won the World Cup with his national team, was voted best player, and got the golden boot for the highest number of goals scored (which was also six, like Kempes in 1978). It is the Italian Paolo Rossi, but his story is even more formidable. Rossi was involved in a betting scandal known as Totonero in 1980 and was banned from playing soccer for three years. He should therefore not have participated to the 1982 World Cup. However, his ban was reduced to two years and the coach of the Squadra Azzurra, Enzo Bearzot, not only selected him for that World Cup while he did not play much before it, but also put him on the field for the group matches despite his poor shape. It was an absolute disaster. Italy tied its three first games and qualified by the skin of its teeth, namely by having scored only a single goal more than newcomer Cameroon. Rossi’s performance was described as follows: “a ghost aimlessly wandering over the field’’. Bearzot continued to give his trust to Rossi against the Argentina of Kempes and Maradona. Italy won 2-1 but Rossi was still the shadow of the player he was before 1980, and the next match was against the “Samba team’’ of Brazil that was simply amazing to watch and that just needed a tie to qualify to the semi-final. Surprising everyone, Rossi scored as early as the 5th minute, but the great Socrates equalized. Rossi then made the net shake a second time at the 25th minute, but the genial Falcao answered him at the 68th minute. Six minutes later, Rossi had his third tally of the day, and Italy caused an enormous shock by eliminating one of the best football teams ever. To understand how Rossi broke the hearts of millions of Brazilian fans, the following true anecdote must be told: many years later, Rossi went to Brazil and took a taxi from the airport to reach his hotel. While driving, the taxi driver looked at him and asked him if he was Paolo Rossi. After hearing the positive answer , the taxi driver stopped his car and simply said: “please get out of my taxi’’. After his legendary game against Brazil, Rossi continued his spectacular return, by scoring twice against Poland in semi-final for a 2-0 win and then the first goal of the final during the 3-1 triumph against West Germany. Paolo Rossi has thus put the ball at the back of the net six times in a row for Italy in only three games. The ghost Rossi had become the Phoenix of the mythology who was born again! This phoenix even won the 1982 Golden Ball thanks to this resurrection.

Another Italian striker came from nowhere to shine a new light in the soccer sky during the 1990 World Cup in Italy. Salvatore “Toto’’ Schillaci, who was born in Sicily and played for Juventus at that time. He was simply considered as the substitute of the reliable Andrea Carnevale from Napoli and the “goal twins’’, Gianluca Vialli and Roberto Mancini from Sampdoria. Schillaci had never played for Italy before in competitions between national teams. The Italian coach, Vicini, decided for a Carnevale-Vialli front line for the first game against Austria. Schillaci substituted Carnevale at the 75th minute and found the net only three minutes later, securing a 1-0 win for Italy. Carnevale-Vialli was still the preferred choice of Vicini for the second game, barely won 1-0 by Italy against the United States thanks to a goal of Giannini. However, for the third game against Czechoslovakia, Vicini changed his mind and put the brilliant Roberto Baggio from Fiorentina alongside Schillaci as the two forwards. These two players thanked the coach by scoring each one goal for a 2-0 win. Schillaci then followed his fate in the knockout stage by having a tally in each of the following games: when Italy eliminated Uruguay by 2-0 in the round of sixteen; in the quarter final won 1-0 against the Republic of Ireland; in the semi-final where the Argentina of Maradona defeated Italy on penalty kicks after a 1-1 tie; and in the third-place play-off for a 2-1 victory against England (with the second Italian goal being made by Baggio). Like Rossi eight years before, Schillaci was the top scorer of the 1990 World Cup with six goals and voted its best player. On the other hand, Schillaci neither won the World Cup with Italy nor became Golden Ball from the France Football magazine that year (he finished second behind the German World Cup winner Lothar Matthäus), unlike his illustrious predecessor. However, his story is still remarkable. Like Kempes, Schillaci did not have too much luck with his national team after his successful World Cup since he only scored a single goal for his reminding matches with the Squadra Azzurra.

To conclude, one must mention the Brazilian Ronaldo and his 2002 World Cup held in Japan and South Korea. The true Ronaldo (as the Portuguese coach Mourinho once said to vex his compatriot Cristiano Ronaldo) was simply extraordinary and fully deserved his nickname of “Ô Fenômeno’’ [the Phenomenon] as soon as he started playing with professional teams at the young age of 16. On the other hand, he was kind of unlucky during his first two World Cups in 1994 and 1998. For the first one that Brazil won, he did not play a single minute because the coach, Carlos Alberto Parreira, feared he was too young at 17 and because there were already two remarkable forwards with Romário and Bebeto. For the second one, Ronaldo was spectacular and was voted best player at 21 but suffered a convulsive fit just hours before the final against the home country of France. Surprisingly and shockingly, he still played that final, which may explain that he was not as good as usual, and that France easily won 3-0 that game. By the age of 23 in 1999, Ronaldo has already scored more than 200 goals for his country and club and was chosen as the 1997 Golden Ball by France Football (which still makes him the youngest winner ever for this trophy first awarded in 1956). However, he then had a series of injuries that basically prevented him from playing for the next three years. The coach Luiz Felipe Scolari still called him to be part of the Brazilian team that competed in the 2002 world tournament. Ronaldo adopted a very strange haircut during that tournament in order that journalists asked him questions about his hair rather than about his recurrent injuries and level of fitness. While Ronaldo was not anymore the fast and furious forward the world of soccer has witnessed before all his injuries, he remained an incredible striker. He found the back of the net eight times during the 2002 World Cup, including the two of the 2-0 win of Germany in the final, making it the top goal scorer. He also received the 2002 Golden Ball from France Football for his exploits during that tournament.

All the stories detailed here naturally call for the selection of the best quote about destiny and/or fate. Which one would that be for you? For me, nothing beats the one of Groucho Marx saying, “Man does not control his own fate. The women in his life do that for him’’, but the relation between the Marx brothers and soccer will be the subject of another upcoming article.

Laurent Bellaiche is a Distinguished Professor in the Physics Department and Institute for Nanoscience and Engineering, as well as the Twenty-First Century Endowed Professor in Optics, Nanoscience and Science Education (for more details, please see: ccmp.uark.edu). His favorite team is Paris Saint-Germain, especially that of the first trophies (French Cups) in the 1980’s, with the three Dominique’s (Baratelli, Bathenay and Rocheteau) and two jewels (Safet Susic and Mustapha Dahleb). His two favorite male football players of all time are Diego Armando Maradona and Robby Rensenbrink. His current three favorite female players are Grace Geyoro, Melchie Dumornay and, of course, Sophia Smith. His favorite soccer/football quote is one from Bill Shankly, “Some people think football is a matter of life and death – I assure you, it’s much more important than that.”