Last year honors civil engineering major Juan Andrés Martínez Castro went to a Seattle career fair in search of an internship. While he was there, an advertisement for work at the Panama Canal caught his eye. “I was looking for things here in the U.S.,” he said, “but I never thought about my own country.” Juan is from a small village called Macaracas, in the province of Los Santos in Panama. After consulting with his advisors, Drs. Findlay Edwards and Clinton Wood, he applied for the job and soon found himself in his home country, working at the Miraflores Water Treatment Plant at the Panama Canal. Once there, he engineered a simple solution to a vexing problem at the Miraflores Water Treatment Plant, whose filters were coming up against an unusual volume of sludge.

From 2009 to 2016 construction was underway on a major expansion of the Panama Canal. Among other updates, the new canal is deeper and longer than the old one, and now, a portion of the water used in the canal is recycled back into the system, rather than released straight into the ocean. While these are much-needed changes, the digging and dragging of soil during the construction process increased the turbidity, or murkiness, of the water, which put a strain on the Miraflores filters. Even without this added strain, however, the two-layer filters used by the treatment plant, comprised of a layer of anthracite on top of a layer of sand, had been steadily decreasing in efficiency since the 1990s – a filter that once had to be cleaned only 14 times a month is now being cleaned, on average, more than 40 times a month. Juan’s primary research goal was to discover the cause of this loss of efficiency.

Miraflores has been supplying 50 million gallons of water to Panama City every day since 1913. “Water is not the main resource for the Panama Canal,” Juan said, “but it is the most important thing for the canal, because without water it cannot work at all. And with the new Panama Canal we need more water for every transit, so that was really important. I was not only working for the water treatment plant but also learning how to take care of the water itself.”

Here, Juan is measuring the turbidity of the water in the canal. The technology he used for this aspect of his research is modern, but when he was acquiring floc samples, he used the same tools Miraflores has been using for decades. “It still worked great. What I love about the Panama Canal is that they keep the essence of the past and also merge that with the future.”

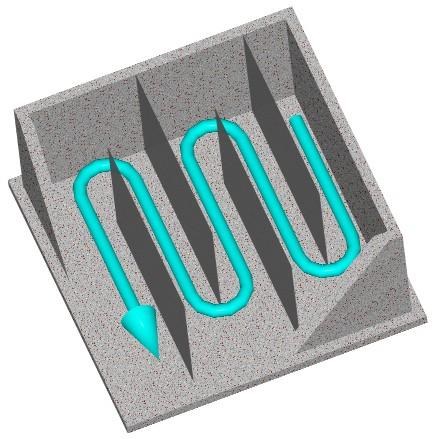

Working with the geotechnical division of Miraflores, Juan did an analysis on the floc (mud and sediment) particles that were filtered out of the water in the sedimentation chambers of the treatment plant. He created small models of both the dual-layer filters (above) and single-layer sand filters like the ones the plant used prior to the 1990s, and discovered that the sand filter was actually more efficient than the filter with both sand and anthracite. He hypothesized that this was because the two-layer filters worked well in the past due to what was called Filter A – Polymer 818, which helped flocs coagulate to form larger particles, making them more likely to be caught by the filters. Without this polymer, which was withdrawn in 1999 when the Panama Canal was turned over to Panamanian control by the United States, the mud is unable to undergo the flocculation process, and the finer particles are less likely to be trapped by the filters.

Juan’s solution was a simple one: “I was…looking at data for days and days and days trying to figure out what was happening [with the filters], when actually the problem was just at the beginning of the process.” He proposed a modification to the flow route of the water within the sedimentation chambers of the treatment plant. By adding walls throughout the chamber, the water can flow like a long line at a ticket office, weaving back and forth and increasing the distance the water travels through the filters. Increasing the flow path in this way increases the flocculation by allowing the chemicals more time to act on the water.

Juan considered himself lucky to get to visit the clearwell chamber, which is the final chamber the water filters into in the treatment plant — he was the first student to set foot in the area, and the last time it was opened was in 2001. It took so much work to open the chamber, they weren’t able to enter until 3:00 in the morning.

Juan had other duties at Miraflores that he hadn’t anticipated: for example, boarding ships to make sure they met the proper measurements to pass through the Canal, and that the crew and captain understood the procedures. He also taught the workers at Miraflores how to use some of the equipment for the wastewater treatment plant — when they built the new Panama Canal, they also built a new system for treating water, and all the equipment came with English instructions. Juan translated these instructions into Spanish. “I thought that was pretty cool. People were asking me questions instead of me asking them questions, so that felt kind of great.”

Manmade Gatun Lake both provides water for Panama City and serves as part of the waterway for the Panama Canal. Here, trees at the bottom of the lake poke through the surface. This is one of the effects of the dry season, which came about due to climate change. “If we learn how to actually take care of water, we may have water in the future. We take it as a given that we will have water every day, but that might not be the case forever. So working at Miraflores actually has changed my habits and how I consume water.” Juan says that turning off the tap while you’re brushing your teeth, or filling the sink with soapy water and clean water instead of keeping the water running while you’re doing the dishes, can have a huge impact. “You might think this is a small change, but if everyone does it we can save millions of gallons of water a year.”

One of the best things about working in Panama, Juan says, was being able to spend a significant amount of time with his family, whom he usually only gets to see once or twice a year. The thing he misses most when he’s away? Patacones, green plantains fried in large chunks, then smashed and fried again. “They’re like our French fries,” he laughs. “And then with ceviche…ceviche from Panama, fresh fish…it’s amazing.”

U of A honors students are changing the world! Miraflores is set to make a project proposal for the implementation of Juan’s clearwell design next year.