By Daniel Kennefick and Laurent Bellaiche

According to the Old Testament, Moses is the leader of the Exodus and showed the Hebrews the way toward the Promised Land. However, he was not allowed to enter this land, unlike his people.

One wonders if figures like Moses exist in the world of football. In other words, does the history of football include players who were recognized leaders of their nations but did not witness one of their greatest moments of glory?

Since there were 12 Hebrew tribes who settled in different parts of Canaan, we are going to provide 12 examples of players who qualify as “a Moses” of football.

Since Frenchmen were behind the creation of the World Cup (Jules Rimet) and the UEFA European Championship (Henri Delauney) of football, as well as the Olympic Games (Pierre de Coubertin) between countries, let us start with a unique and remarkable French player. His name is Marius Trésor and is so famous in France that just saying his first name is enough for any French fan to recognize him. Marius was born on Jan. 15, 1950 in the French Caribbean Island of Guadeloupe. At the age of 19, he played professionally for Ajaccio, a city located in the French island of Corsica. He competed there in the French top division. His exceptional talent as a central defender, in general, and his sliding tackles, in particular, were so impressive that he earned his first selection for France in December 1971 against Bulgaria in Sofia for a 2-1 defeat. The year after, he was voted the best French player of 1972 and also joined one of the giant clubs in French football, Olympique of Marseille, with which he won the French Cup in 1976 as the team captain. This year of 1976 also saw him wearing for the first time the armband for the French national team, once again in Sofia, Bulgaria for a 2-2 tie. This game is a classic in the history of football because a famous French journalist, Thierry Roland, was furious against many highly controversial decisions of the Scottish Referee Ian Foote against Les Bleus. Thierry Roland then declared on TV, “I am not afraid to say it. Mister Foote, you are an asshole.” This interesting characterization of the Referee’s qualities had two consequences for Thierry Roland: he was suspended and forbidden to comment on football events on TV for some months while at the same time, he became a national hero. But let us come back to Marius Trésor.

Among many wonderful games played for the National team, two occasions stand out. The first one is against Brazil in June 1977. For the first time in its history, France is playing in the Maracana, which is a temple of football located in Rio. Marius is leading the team, but France is trailing 2-0 after 51 minutes. One minute later, the gifted left winger, Didier Six, reduces the score for France via a brilliant chest control of the ball followed by a volley. In the 85th minute, France gains a corner kick. Like Icarus, Marius flies at an incredible height when the corner is kicked. He does not burn his wings but rather strikes the ball with a powerful header, to allow France to secure a tie in this famous Brazilian temple. The French captain has spoken not with words but with actions. The second highly memorable moment of Trésor in the French jersey is the Danté-esque semi-final of the 1982 World Cup against his country’s arch-rival, West Germany. The German elf, Pierre Littbarski, opens the scoring in the 18th minute. Michel Platini, who is often considered the best French player of all time, ties the game with a penalty kick. After 90 minutes, the score is still 1-1. Extra time is needed. Only three minutes into extra time, Marius scores with a splendid volley. 2-1 for France, a score, which soon becomes 3-1 after Alain Giresse shoots with the outside of his right, sending the ball in off the post. With only 21 minutes left to play, France has a two-goal advantage. Optimism is rising high for the French fans, but West Germany rallies first in the 103th minute with a Rummenigge goal and then in the 108th minute with one by Fisher. The series of penalty kicks will decide the winner of this hard-fought battle. It will be Germany by 5-4, to the utter despair of an entire generation of Frenchmen. Marius Trésor subsequently plays only one more year for France. His last game is against Yugoslavia in Zagreb in November 1983. This was his 65th cape for Les Bleus, a national record at that time. Marius will then retire from football at the end of the 1983-84 season, having helped his last club, Bordeaux, win its first French championship since 1950 (the year Trésor was born). Because of multiple injuries during the latter years of his career, Marius did not participate in the 1984 Euro competition organized in France from June 12 to June 27, 1984. And what happened? France won its first-ever international competition, just a few months after one of its most effective and beloved leaders retired from international football!

Another player born in Guadeloupe and having worn the jersey of Olympique Marseille, Jocelyn Angloma, also missed French glories. Angloma decided to stop playing for the French National team after the 1996 Euro competition when he lost his spot in the starting eleven to a third defender from Guadeloupe, Lilian Thuram. Unlike this latter, Angloma was therefore not part of the French team that won the 1998 World Cup and the 2000 Euro, while he was still playing at a high level. For instance, he participated in (but lost) three finals in European club competitions from 1997 to 2001. One with the Italian team of Inter Milan and two with the Spanish club of Valencia.

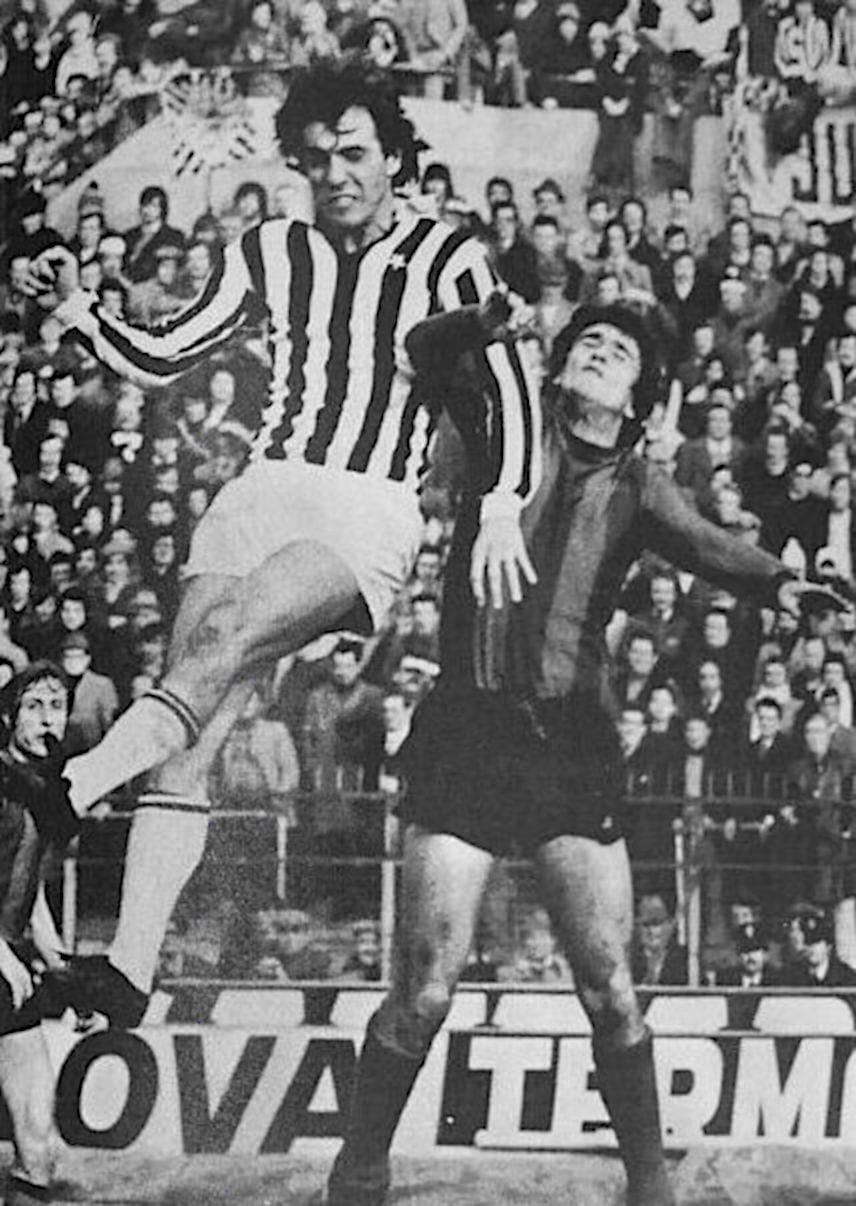

Speaking about Italy and Spain, they also each have a player that can be considered as the Moses of his country. The Italian one is Roberto Bettega, often nicknamed Bobby Goal for shaking the net of many an opponent or La Penna Bianca (White Feather) because of his grey hair. Like Marius, Roberto was also born in 1950. While in Italy, he played solely for Juventus, from 1969 to 1983, and won seven Serie A titles as well as the 1977 UEFA Cup. This formidable forward was a member of the Italian National team from 1975 to 1983 and had a tally of 19 goals in 42 games for the Squadra Azzura. Italy with Bettega finished fourth at the 1980 Euro organized in its own turf, and fourth again at the 1978 World Cup located in Argentina. During that latter World Cup, he even scored the sole and winning goal against the home team of Argentina during the final game of the first round group and was elected in the FIFA World Cup All-Star team. Unfortunately, a knee ligament Injury prevented Bettega from competing in the 1982 World cup. Can you guess what happened there? Italy became world champion again, 44 years after its last victory in 1938 when Mussolini was still holding power.

Regarding the Moses of Spain, a legend of Real Madrid, Raúl González Blanco, is a serious candidate to consider. This Spanish forward, generally simply called Raúl, is born in 1977 and played for La Casa Blanca (nickname of Real Madrid) for 18 years, from 1992 to 2010. While there he won six Liga, three UEFA Champion’s Leagues and two intercontinental cups. He is the player that has worn the Real jersey the most times (741 in all) and has scored over 200 goals for that mythical team. Regarding his relations with his national team, he was called 102 times for Spain, tallying 44 goals, between 1996 to 2006. He competed in three World cups and two Euros during this 10-year period, with the highest finish being two quarterfinals both lost, one against France at the 2000 Euro and another one against South Korea at the 2002 World Cup. A huge surprise came in 2008 when the Spanish Coach, Luis Aragonés, did not include Raúl in the group to compete in the Euro held in Austria and Switzerland. Not only did Spain become European champion that year (44 years after their last and only victory in 1964), but also successively won the next World Cup in 2010 and the next Euro in 2012; without Raúl.

Other football powerhouses also possess their own Moses. For instance, Brazil had a prolific goal scorer named Careca and a very solid defender and leader with Ricardo Gomes. Careca is born in 1960 and scored 30 goals in 64 games for the Auriverde between 1982 and 1993. He is also famous for having won the 1989 UEFA Cup and the 1990 Italian championship with Naples, alongside Maradona. Ricardo Gomes was born in 1964 and played for Brazil between 1984 to 1994. He is also considered one of the best players in the history of the French team of Paris Saint-Germain, with one French championship, two French cups and one French League cup won between 1993 and 1995. Both Careca and Ricardo Gomes missed the 1994 World Cup held in the U.S., which Brazil won. The situation was worse for Ricardo Gomes because he missed it for injury, being removed at the last minute, while he was the captain of his national team.

Germany is not exempt from having a leader missing moments of glory. Stefan Effenberg, born in 1968, was known for his leadership, his physical strength and powerful kicks. He won numerous awards with Bayern Munich, including three Bundesliga, one German Cup, one Champion’s League and one Intercontinental Cup. He was called for National duties 35 times between 1991 and 1998. He was therefore a little bit too young to compete in the 1990 World Cup that Germany won. On the other hand, he was the right age to be able to play in the 1996 Euro where Germany triumphed too. However, Effenberg was not called upon for the Mannschaft that year, due to his controversial character and having given the finger to German fans during the 1994 World Cup. He did play at the 1992 Euro in Sweden, but Germany surprisingly lost 2-0 to Denmark in the final.

This latter success is simply one of the most extraordinary moments in football history for multiple reasons. First of all, Denmark did not qualify for that Euro. They finished second in their qualifying group behind Yugoslavia. However, this same East European Nation was banned on May 31 from playing in the 1992 Euro because of the ongoing war there. Denmark was therefore invited to take part only 10 days before the beginning of the tournament! This Nordic country had to call players who were on vacation and arrived without any hope of doing well in the competition. They even organized parties every single night during the competition. But miracles happened that year: Denmark first qualified for the semifinals by finishing second in its group behind Sweden, eliminating no less than the France of Cantona and Papin and the England of Lineker. They then defeated on penalty kicks the previous Euro winner, the Netherlands of Bergkamp, Riijkard, Gullit and Van Basten; before finally triumphing against the current World Champion, the Germany of Brehme, Sammer, Klinsmann and also Effenberg. What is also highly surprising is that Denmark won this prestigious European Championship without their best player, Michael Laudrup. This Danish midfielder or forward is without the slightest doubt one of the best footballers that this Scandinavian country has ever produced. Born in 1964, he was even named Denmark’s best player of all time in 2006. He was champion with clubs in three different countries: In Italy with Juventus in 1986, in Spain five years in a row with Barcelona and then with Real Madrid between 1991 and 1995 and in the Netherlands with Ajax in 1998. His elegance and intelligence on the field are hard to match. He played with the Danish dynamites for 16 years from 1982 to 1998 for a total of 34 goals in 104 games. However, he refused to be part of the 1992 Euro because of the style of play of Denmark at that time, while he was still one of the world best players. The incredible success of Denmark at this Euro therefore makes Michael Laudrup the Moses of his country, doesn’t it? Ironically, his younger brother, Brian Laudrup, took part at this Euro and helped Denmark to their shocking victory.

The African continent is by no means exempt from having their own Moses. A striking example is Didier Drogba. Born in 1978 in Abidjan, in Ivory Coast, he then migrated to France at the early age of 5. After returning briefly to Abidjan, he went back to France where he played first in the lower divisions. When he was 20 years-old, he joined a second division team, Le Mans, where he stayed four years. In 2002, he was transferred to another small team, Guingamp, but they were playing in the first division. His career then took off during the 2002-03 season where he scored 17 goals in 34 games for that team from Brittany. As for Trésor and Angloma decades before, Drogba then joined Olympique Marseille for the 2003-2004 season. He was simply outstanding both in the French league and in European competitions. He was named the Player of the Year in France. The English club Chelsea then acquired him during the 2024 summer for an astronomic fee of 24 million pounds. They never regretted it: under his guidance, Chelsea won four English Premier Leagues, four FA cups and a UEFA Champions league (in 2012). Drogba scored the goal for Chelsea during the 2011-2012 final of that Champions league, that ended after extra time in a 1-1 tie against the giant Bayern in Munich. He then scored the winning penalty during the penalty shootout to give Chelsea its first ever UEFA Champions league. Drogba also wore the Ivory Coast jersey 105 times, a record number of goals of 65, from 2002 to 2014. He was the captain of this African nation but never won anything with it, losing on penalty kicks to Egypt and Zambia the finals of the 2006 and 2012 Africa Cup of Nations, respectively. And what happened one year after Droga stopped playing for the Ivory Coast, in 2015? The Ivory Coast brought home for the first time since 1992 the Africa Cup of Nations, of course!

All of the Moses examples we have given so far played for countries that have won major trophies. But Moses was the leader of a small tribe, one which never vied with the great empires of the middle east for the title of King of Kings, but sought only its own small place in the Sun. What of the countries for whom qualifying for a major tournament is a goal, and a rare event, in itself? How much more painful must it be to miss out on one of the few opportunities, which footballers from those small countries ever see to perform on the big stage? Furthermore, small countries do occasionally produce great footballers, and consider how unique is the role of one of these big fishes in small ponds, shouldering the burdens of their countrymen’s expectations when it is inevitable that everyone around them, including their teammates, is looking to them as the leader who can take them to the promised land? Consider also that the Jewish people have famously had three Moses figures throughout their history, the original Red Sea pedestrian, but also Moses ben Maimon, known in Europe as Maimonides, the greatest medieval Jewish scholar, and the greatest figure in the entire rabbinical tradition and finally Moses Mendelssohn, the senior figure in the 18th-century Jewish enlightenment that gave birth to modern Judaism (and, yes, the grandfather of the composer Felix). Now consider the case of the three Moses of Irish football.

The first of these was Johnny Giles, a skillful but combative footballer, who was one of the key figures in the great Leeds United team of the 1960s and ‘70s. Giles was also a student of the game who came to manage the Republic of Ireland’s national team while still playing for it in the 1970s. Ireland is both a small, poor country and one in which association football (“soccer” as it is often known in Ireland) is not the major sport. Furthermore, most sport in Ireland is organized on an amateur basis. Soccer is, at best, semi-professional, and professional footballers typically ply their trade elsewhere, as Giles did. As such, Irish teams traditionally had an approach characterized by the phrase, “give it a lash,” meaning leave it all on the pitch, but don’t worry too much about preparation, planning and professionalism. Giles, as player and manager, sought to change all that. Though Ireland had never qualified for the finals of a major tournament (meaning the European Championship or the World Cup), Giles was arguably the first to conceive the ambition of building towards that. In 1977, as player-manager of an emerging Irish team, he led them to victory over a fine French side at Lansdowne Rd. in Dublin. France eventually went through but had a scare in a tight three team group (the other team was Bulgaria). This was as close as Giles would ever get to the World Cup, but remember that the original Moses never got close to the promised land either, seeing it only from a mountaintop afar. Such was Giles’ fate. But he passed the baton anyway. In 1977 against France, he drove an early free kick from distance, which was partially cleared by the head of a French defender. The ball fell kindly for a young Liam Brady who dribbled through and toe-poked the ball under the advancing ‘keeper.

Liam Brady is then, our central Irish Moses figure. One of the best players in Europe in his heyday with Arsenal, Juventus, Sampdoria and Inter Milan, he was also an untypical figure in Irish football, a player who played the beautiful game with skill and finesse, in a country that values effort, commitment and combativeness on the pitch. The Irish admire skill, but typically prefer an all-action direct style, occasionally characterized by the famous doctrine of “route one,” pumping the ball up the middle of the field towards the goal and chasing it. “Chippy” Brady was not an advocate of route one. He was known for his delicate touch with his cultured left foot, though his right foot was “solely for standing on.” It is often thought that his nickname derived from his renowned ability to “chip” the ball over advancing ‘keepers, but in fact, it originated from his devotion to the national dish of the urban Irish, chips (French fried potatoes).

Inheriting from Giles a promising team and an ambitious objective of major tournament qualification, Brady was the undisputed leader of the Irish national team for a decade between 1978 and 1988. His greatest moment was the qualification campaign for the 1982 World Cup. Brady was at the height of his powers, and he had a decent team around him. Unfortunately, he also faced perhaps the most difficult World Cup qualifying group ever assembled, which consisted of: 1) France (again), the great French team evolving towards the Carre Magique era, which would romance the footballing world at the next two World Cups and win the European championship of 1984; 2) a great Belgian team, which had finished runners up at the previous European Cup and would perform at a high level at the next two World Cups; 3) The Netherlands, fresh from two tilts at the World Cup final itself. Ireland gave a superb exhibition in this group, winning all their home games save for a draw against Belgium, knocking out the Dutch with a draw in Rotterdam, and almost beating the Belgians in Brussels – succumbing to two dodgy refereeing decisions, which saw the only Irish goal incorrectly disallowed, while the winning Belgium effort, scored at the death by the great Jan Ceulemans, resulted from a free kick awarded for an obvious dive (the Irish fans would have appreciated of a few words from Thierry Roland after that match!). Once again Ireland beat France at home, this time on a 3-2 scoreline in which Ireland traded skillful move for skillful move with a marvelous French team. In the end, the Irish went out on goal-difference to a French team, which moved on into immortality. Brady had reached the very border of the promised land, but would he ever cross over?

Enter an old teammate of Giles, English world cup winner Jackie Charlton. Unexpectedly appointed manager of Ireland in the mid-80s, Charlton inherited an excellent squad, full of players who not only played for top division one teams in England, but were mostly stars for those teams. This was an unheard-of scenario for an Irish team, one which was brought about by a combination of generational good fortune (the likes of Brady, Liverpool’s Ronnie Whelan, Arsenal’s David O’Leary and Paul McGrath, Kevin Moran and Frank Stapleton of Manchester United were all available, and homegrown) and an increasingly deliberate tactic of persuading British born players with Irish ancestry to declare for Ireland (which bore fruit in players of the caliber of Liverpool’s Mark Lawrenson, Ray Houghton and John Aldridge and Everton’s Kevin Sheedy). Charlton had no patience with the underdog Irish mentality, though the distinctively British style of play, based upon high pressing, which he favored was familiar enough. This meant that a traditional phrase came to be forever associated with his name, in the form “give it a lash, Jack” along with “put ‘em under pressure.” Playing against Ireland was going to be “90 minutes of Hell” before a similar phrase was even heard of down Arkansas way.

But there was one fly in the Irish ointment. The high press demanded complete commitment from every player on the pitch. Brady, used to being exempted from such strictures as the playmaker on top club teams in England and Italy, and no longer a spring chicken, was not the ideal player to feature at the center of Charlton’s team. But could a manager really not select the greatest player ever to play for his country? In the qualifying campaign, it seemed as if this circle had been squared. Brady did feature, and the Irish pressed for Charlton and found success. Fortune smiled on Charlton’s team as the qualifying group was by far one of the easiest Ireland ever had the good fortune to be drawn into. Unusually, none of the large European countries featured, and the main opponents were Belgium (again, though now a little past their best), Bulgaria (again, but this time at their peak, featuring Hristo Stoichkov) and near neighbors Scotland. Ireland competed well but needed to win the group to qualify (as was usually the case in those days). Despite a key away victory at Hampden Park in Scotland (where Mark Lawrenson scored the winning goal playing from midfield, but later endured a Moses ending of his own when injury ended his career before he could join Ireland in the Finals), it seemed as if they would fall just short again. Bulgaria needed only a home draw to Scotland in their final game to secure the only qualification spot at Euro ’88. But the Bulgarians, failing to find the net against typically dogged Scottish resistance, began to play for the draw and fell victim to a late sucker punch as Gary McKay, of Edinburgh’s Hearts, scored a late goal to put Ireland, unexpectedly, through. For the first time ever, Ireland had qualified for the finals of a major tournament. The promised land had been reached!

What then, of our Moses? While Brady was the kind of footballer for whom the word “cultured” might have been invented (Nick Hornby devotes a long passage of his famous book “Fever Pitch” to a paean of Brady, describing how Brady made him feel that it was okay to be an intellectual who happened to be a football fan) he was a true Irishman, passionate, committed and combative. In Ireland’s final group game against Bulgaria, won 2-0 thanks to goals from Dubliners Paul McGrath and Kevin Moran (two center backs in an Irish team overloaded with them, given the additional availability of David O’Leary, Mick McCarthy and Mark Lawrenson), Brady earned a rare sending off. Man marked as usual, he became frustrated late in the game and lashed out at his Bulgarian counterpart, pushed him away a little over-zealously so that his forearm flung out and caught his opponent in the face. Irish people everywhere, used to the vigorous challenges of hurling, rugby and Gaelic football, scornfully declared that the poor Bulgarian “made the most of it,” with a theatrical fall to the turf. Nevertheless, the referee was quick to show Brady a red card. Brady didn’t help himself by directing a very insulting gesture with his forearm to the official’s back as he left the field (or perhaps this was meant for the Bulgarian?). At any rate, UEFA handed Brady a four-match ban, reduced on appeal to two. This still left the prospect of Brady’s participation in the final Irish group game at the Euros, against familiar foes, the Netherlands, but then calamity befell. Brady, then playing for West Ham United in the English league, ruptured his cruciate ligament and was conclusively ruled out of contention for the Finals. Thus, Ireland’s greatest player missed out on one of his country’s greatest achievements, the victory over England in the first match at the tournament, 1-0, the famous goal scored by Ray Houghton, a native-born Scot doubtless as happy as any of the Irish players to defeat the “auld enemy.”

There might still have been time for Brady to reach the promised land, in spite of his advancing years. Ireland qualified for the World Cup, again for the first time ever, in 1990. But time and the tactical scheme of his manager was against him. In a friendly against West Germany in 1989 Charlton, presumably unhappy with the level of pressing from his aging playmaker, substituted Brady after only half an hour. At halftime Brady let Charlton know, in no uncertain terms, of his unhappiness, and words were exchanged. Feeling that there was now no chance of being selected for the World Cup squad, Brady elected to retire after that match. He has since revealed that Charlton subsequently wrote to him to patch things up and offered to take Brady to Italy with the World Cup squad, but Brady perhaps didn’t fancy making up the numbers where he had once been the first name on the team sheet. At any rate, it meant that he would indeed be a true Moses figure for Ireland: A player who guided his country to the gates of the promised land, but never did leave even a single footprint on its soil. It was also not the last time that a shouting match in the Irish dressing room would prevent one of the country’s footballing heroes from featuring at the World Cup.

Liverpool’s Steven Gerrard vs. Manchester United rival Roy Keane. (Photo by world_pictures 77 https://flic.kr/p/dTaoFT)

Our final Irish Moses, Manchester United’s Roy Keane, lived to witness the expulsion of the Irish from the Promised Land. Just as the Jewish people did find their way to Canaan, only to lose it once again in the diaspora, so the Irish, after enjoying a brief period of regular appearances in final tournaments and once again enduring many years of failing to qualify for the World Cup. Keane started his career in that happy era of regular qualification and played in every Irish game at the 1994 World Cup in the USA, featuring in their famous 1-0 victory over Roberto Baggio’s Italian team, which would go on to lose the final only on penalties (Ireland’s goal in that game was once again scored by the irrepressible Houghton). So, he is not a true World Cup Moses. But his story is nonetheless poignant. In qualification for the 2002 World Cup, he was inspired and imperious. If ever a player embodied the sporting concepts of passion, commitment and combativeness, it was Keane, who at times seemed more like an avatar of those virtues than a mere flesh and blood footballer. Hailing from Cork, rather than Dublin, as was the case for every other Irish-born player mentioned in this article, he carried a burning resentment against the corrupt and inept Dublin-centric leadership of the Football Association of Ireland (FAI), which was typical of citizens of the “rebel city.”

Ignored by Irish youth team selectors for much of his early life, he was the outsider who came to lead his team by sheer force of will. In the run up to 2002, he appeared to bully top-class international teams around the pitch, eliminating a fine Dutch team and securing Ireland’s qualification. In an unheard-of series of competitive successes, Ireland went through the qualification stage undefeated. Keane, whose personal motto was “fail to prepare, prepare to fail” was intent on winning the World Cup, and was horrified at the typically shambolic preparations for pre-tournament training on the island of Saipan in the Pacific. He gave a press interview in which he made his dissatisfaction known. Regrettably, his manager and former teammate, Mick McCarthy, decided to administer a dressing down to his star player during a team talk. The tables were turned when Keane, in a typically fiery outburst, let McCarthy know what he thought of him: “I didn’t rate you as a player, I don’t rate you as a manager, and I don’t rate you as a person. You’re a ********* and you can stick your World Cup up your arse. The only reason I have any dealings with you is that somehow you are the manager of my country!” Most commentary amongst the people of Cork, who were intensely supportive of their native son during the bitter controversy, which followed Keane’s departure from the World Cup squad, centered on the intriguing question of whether the ellipsis in that quotation contained the typical and unique Cork insult “langer,” a word, which is synonymous with the Yiddish “schmuck.” The Saipan incident is still discussed today as one of Irish sport’s great might-have-beens. Despite a creditable performance in the tournament from the slightly less Keane team (top scorer Robbie still featured), Ireland has never qualified for the World Cup finals since, despite several near misses, including the infamous “hand of Henry” incident (encore les Français, toujours les Français!). As the descendants of Moses would say: Still, God willing, it will happen … “next year, in Jerusalem!”

Laurent Bellaiche is a Distinguished Professor in the Physics Department and Institute for Nanoscience and Engineering, as well as the Twenty-First Century Endowed Professor in Optics, Nanoscience and Science Education (for more details, please see: ccmp.uark.edu). His favorite team is Paris Saint-Germain, especially that of the first trophies (French Cups) in the 1980’s, with the three Dominique’s (Baratelli, Bathenay and Rocheteau) and two jewels (Safet Susic and Mustapha Dahleb). His two favorite male football players of all time are Diego Armando Maradona and Robby Rensenbrink. His current three favorite female players are Grace Geyoro, Melchie Dumornay and, of course, Sophia Smith. His favorite soccer/football quote is one from Bill Shankly, “Some people think football is a matter of life and death – I assure you, it’s much more important than that.”

Daniel Kennefick is a physicist at the U of A studying gravitational waves and galactic structure. He is the author of three books on the history of science “Traveling at the Speed of Thought,” “An Einstein Encyclopedia” and “No Shadow of a Doubt,” all from Princeton University Press. Growing up in a sporting family in Ireland he has been a passionate supporter of various forms of football, and other sports, from a young age. He has several family members who were well known players of hurling, gaelic football and rugby. In soccer terms he began supporting Liverpool at a young age, attracted by their winger, Steve Heighway, who played internationally for Ireland. His family emigrated to Canada when he was in grade school, and he can remember going to see the great Pele play for the New York Cosmos against local team Toronto Metro-Croatia. He returned to Ireland after a few years and his chief sporting passion as a teenager and since is Track and Field, both as participant and spectator. He scored brownie points when meeting his future wife and being told she attended the University of Arkansas and he was able to say not “where is Arkansas?” but “oh, that’s where all the (Irish) runners go!”