Honors horticulture student Olivia Hines picks blackberries at the University of Arkansas’ Department of Agriculture’s Fruit Research Station in Clarksville, Arkansas.

Honors horticulture student Olivia Hines has a passion for blackberries, and she’s not just eating them – she’s testing them. Working alongside the University of Arkansas’ blackberry breeding program, a world leader in the development of fresh-market blackberry varieties, Olivia is conducting groundbreaking research on one of Arkansas’ favorite fruits. Guided by her mentors Dr. John R. Clark in horticulture and Dr. Renee Threlfall in food science, the team is using both trained sensory panelists and untrained consumers to evaluate the quality of regional blackberry types. By not only picking, but testing the size and composition of these fruits, Olivia will provide the breeding program with the first report of its kind. Olivia received an Honors College grant, Bumpers College grant and Arkansas Agriculture Specialty Crop Block Grant, all of which continue to support her work.

Today, I accepted an invitation to leave my desk and head to a part of campus that I seldom visit. The Honors College caught word that food science was conducting some pretty interesting research on blackberries, so I set out to learn more. The summer season is perfect for an adventure outdoors – not to mention a welcome break from the academic high seasons. Upon my arrival, I walked into the campus’ Sensory Service Center lab to be met by the largest quantity of picked blackberries I have ever seen (and growing up with a father who considers himself a professional blackberry picker, that’s saying something.)

Here I met Olivia Hines and one of her mentors, Dr. Renee Threlfall. The two welcomed me with coffee and doughnuts, and thanks to Olivia’s Honors College thesis I began to learn more about blackberries than I ever would from behind my desk.

Sweet Satisfaction:

Roughly 90 miles southeast from University of Arkansas campus lies the small community of Clarksville, where the Arkansas Division of Agriculture’s Fruit Research Station maintains a large presence. The research farm spreads across 264 acres planted with apples, peaches, nectarines, strawberries, blueberries, blackberries and muscadine grapes – more than 25,000 plants in all.

In spring 2013, Olivia took a Fruit Production Science and Technology course taught by Dr. Clark – a horticulture professor who just celebrated his 34th year working with the Clarkville farm – and Dr. Curt Rom, horticulture professor and interim Honors College dean. It was here that Clark first noticed Olivia Hines’ enthusiasm for blackberries. So when a project surfaced to investigate fresh blackberries developed in the UA breeding program, Clark contacted Olivia for the opportunity to turn her interest into her undergraduate thesis. Together with Dr. Renee Threlfall in the department of food science, Olivia accepted the challenge.

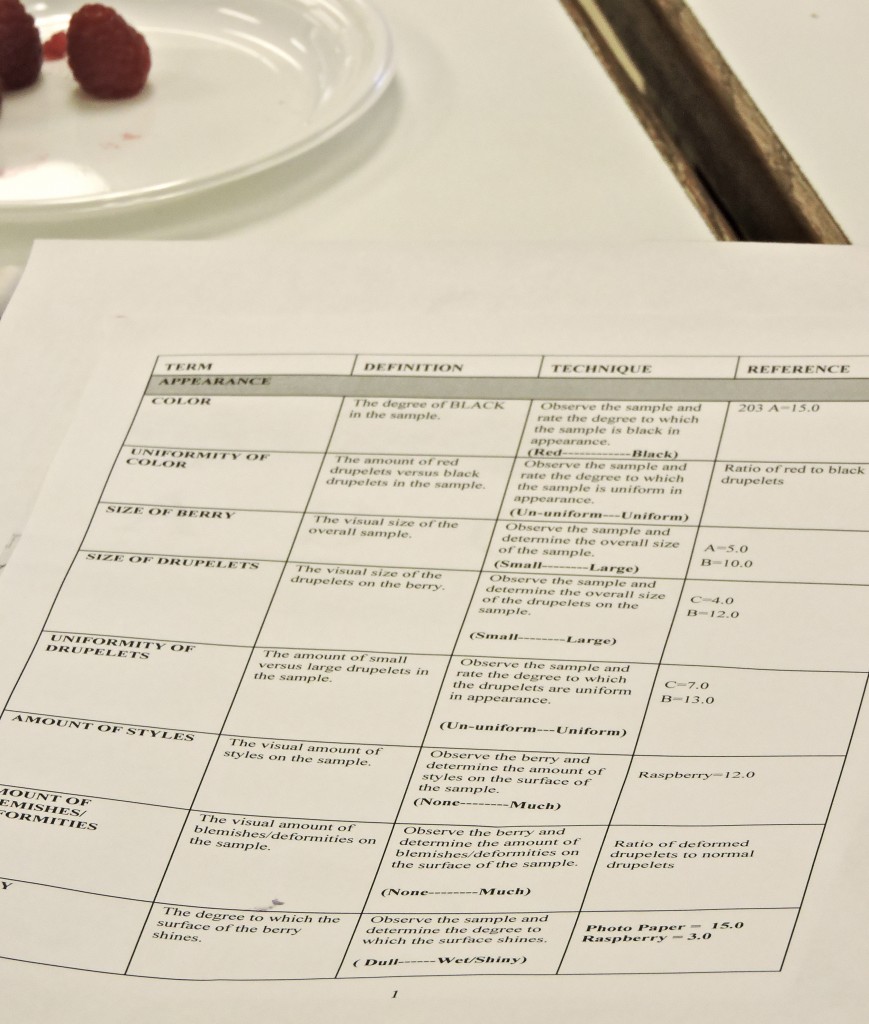

Using the Sensory Service Center in the food science department, this study uses two distinct techniques – descriptive testing and a consumer panel – to assess the quality of the various blackberry genotypes. The day’s pick contains 11 pounds of blackberries per genotype, which includes both named cultivars and advanced selections. In order to become a named cultivar, such as the Ouachita sample below, selections must have at least 10 years of production and testing. There are six different genotypes up for testing today – more than 66 pounds of fruit!

A panel of trained, full-time taste testers rank the blackberry attributes. For statistical purposes, the panelists rank the berries on a 1-10 scale, twice, for each genotype sample.

Olivia and her team hand a sample of blackberries to trained taste-testers for the descriptive panel.

After being evaluated for attributes like size, color and taste by the pros, the blackberries head to the consumers. The Sensory Service Center emailed around 6,500 potential consumers to participate in the panel. Key tools for screening consumers included seemingly-general questions such as: What kind of fruit do you eat? How often do you eat (the indicated fruit)? It’s not surprising that the key answers here were “blackberries,” and a lot of them. Just 96 consumers were selected for the panel, and 76 showed up today for the first round of testing and a complimentary $40 gift card (which they will receive upon their return for round two.)

Consumers receive blackberry samples through a window that connects consumer testing booths to the lab’s kitchen.

Today, tasters receive the first six of the twelve genotypes. Consumers sit in assigned booths and are handed samples of blackberries through a slot window, connected to the sensory lab’s kitchen. This time, testers assess blackberry quality by answering questions involving what they like and dislike about the fruits’ attributes. All samples are blind – that is, consumers do not know whether they are tasting a Ouachita, another named cultivar or an unnamed experimental selection. I participated in a bit of this testing myself, and I can report that my experiences were delicious no matter the sample!

Olivia and her team face unique challenges in their study, many involving the laborious and careful nature of studying fresh fruit. When Olivia picks her samples, she spends almost six hours working on the Clarksville farm. Conditions are hot, dusty and difficult here, as the height of blackberries range from just off the ground to a far reach. After spending the day picking, the fruit must be transported to the Fayetteville campus as soon as possible to ensure the quality and consistency of samples for testing. When I asked Olivia just how fresh these samples were, she told me that she had finished picking just 24 hours before. The process means little rest for Olivia, but there’s always a solution – in the sensory lab’s kitchen, there’s plenty of free coffee to keep spirits and energy high.

Hard work? Yes. Worth it? Yes. Is it done? Not yet! This fall, Olivia will complete the study by investigating the blackberries’ physiochemical properties, otherwise known as the size and composition of the fruit. The information that Olivia and her team collect could have a real impact on developing delicious new cultivars of an old favorite. An honors student is helping lead the pack, and that’s big news in a program already known for pushing the boundaries. Dr. Clark seems to agree. He concludes:

“This is truly groundbreaking work for both the U of A and in the world. Better tasting blackberries mean happier consumers, healthier diets, and help to farmers for growing a profitable crop among other benefits.”

I thank Olivia, her team and the Honors College for the opportunity to share the complexity within Arkansas’ horticulture to the university community and beyond. Best of luck to Olivia and all involved as she continues to break ground and set an example for all of us at the Honors College!