Author Bio: Sydney Nichols is a junior Bob & Ruth Shipley Honors College Fellow majoring in art history and creative writing, minoring in Southern studies. From Marion, AR, Sydney is interested in the artistic and literary expressions of the South. Upon graduation, Sydney plans to pursue a graduate degree in contemporary American art and curatorial studies.

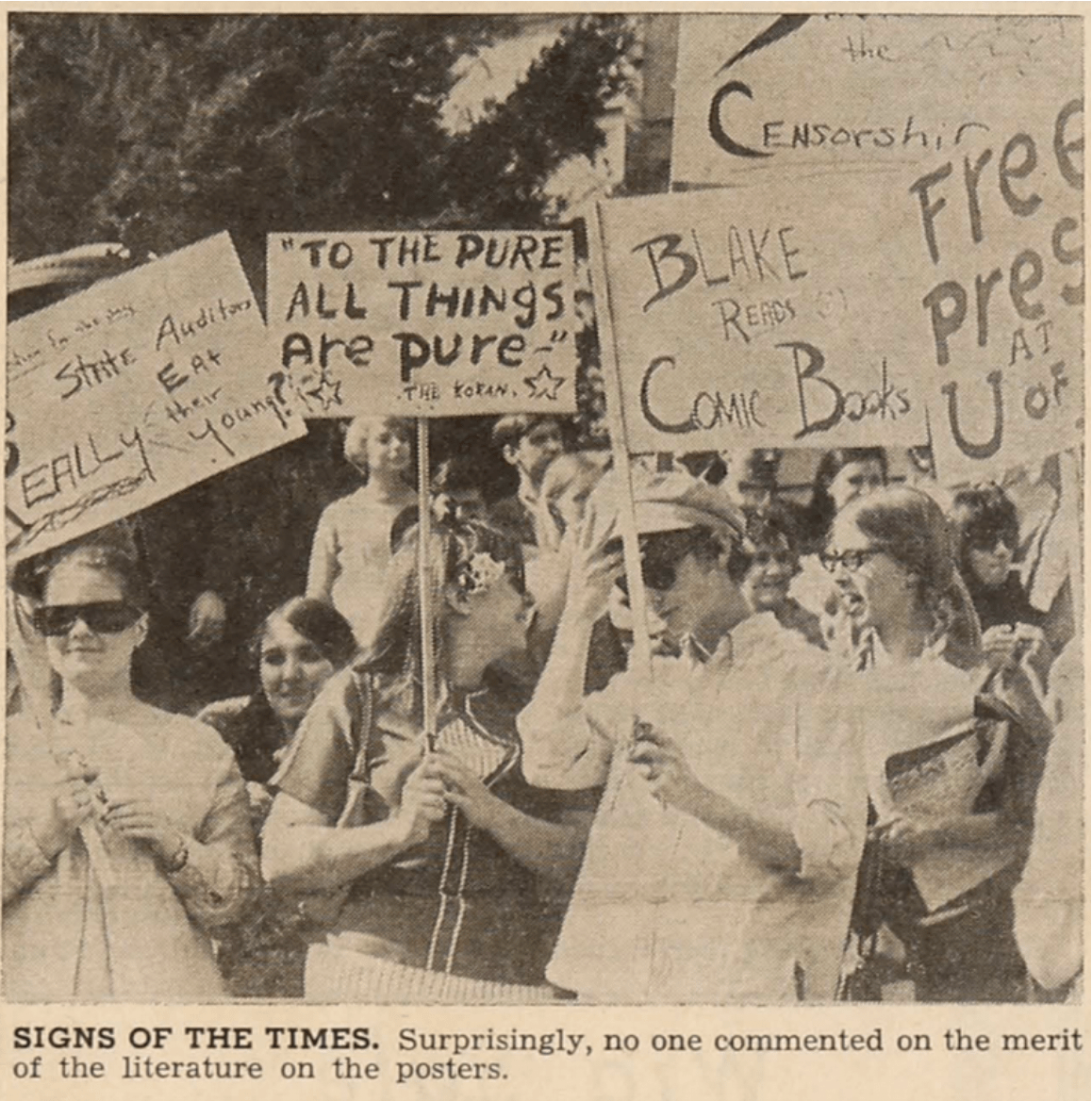

On October 23rd of 1967, as the leaves changed color and fell on the University of Arkansas’s lawns, students gathered in protest outside of the Vol Walker Hall—our campus’s former library. Holding pickets emblazoned with slogans like “Sink the Censorship” and “Viva Preview,” the group of roughly 500 students were calling on university president David W. Mullins to acknowledge his failure to protect the student body’s right to freedom of expression.

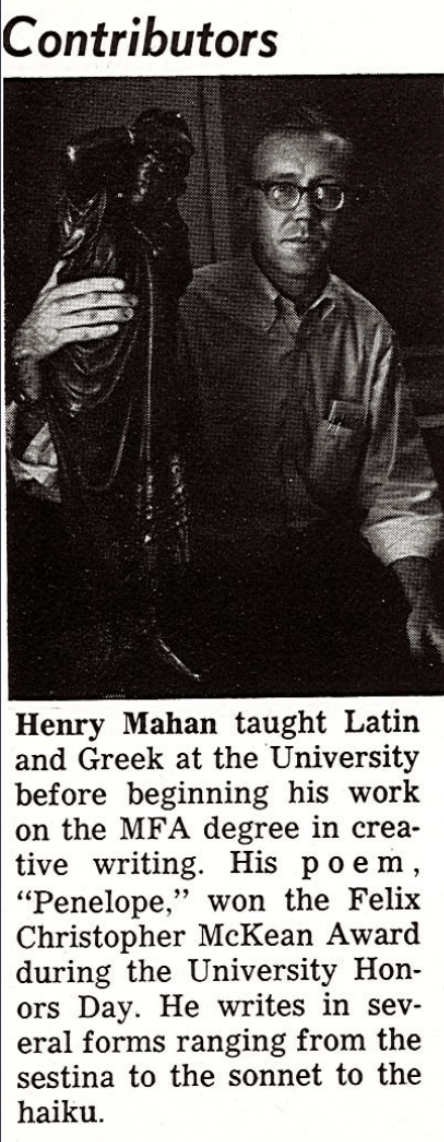

Biography of Preview contributor Henry Mahan. Photo courtesy of the Northwest Arkansas Times Digital Collections.

The animated congregation of students were rallying in support of Preview, the University’s literary magazine published from 1947 through the early 70s. In its final years Preview would feature works by some of Arkansas’s most highly revered writers, including C.D. Wright, Leon Stokesbury, and Frank Stanford. In the fall of 1967, however, the publication’s editors and contributors were struggling to make their writing accessible to their readership. Over eighteen months earlier, in March of 1966, the printing of that year’s edition of Preview was stalled by the influence of journalism department professor and University printing plant supervisor, A.W. Blake. Preview’s editor John Dacus had submitted the compiled issue to Blake for printing, but judging some of the poems as vulgar and fearing that the writing might violate the state’s anti-obscenity laws, Blake refused to move forward with printing until he received approval from a “higher authority.”

The four specific poems that worried Blake were written by Classics teacher and creative writing graduate student Henry Mahan. Described as lewd and “improper for public consumption,” Mahan’s poems sparked a fire that would continue to be stoked by warring opinions of school administrators, state representatives, and members of the student body for nearly two years.

Despite the then dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Dr. Robert F. Kruh granting approval to Blake to proceed with the printing of the issue, the semester’s spring vacation passed without any further progress in its publication. In the interim, Blake had taken the poems to desks of University Council member Ray Trammell and Vice President for Business James E. Pomfret. Both opposed the poems’ publication, intensifying the discord between the University’s administration and the University’s faculty—which largely supported Preview. Over the course of the next month, Kruh assembled a committee of faculty members from the School of Law and the College of Arts and Sciences, intending to resolve the dispute over the poems’ legal propriety. Analyzing the subject matter of all four of Mahan’s poems—including his “Xanthippe’s Apology” and “The Coming of Wisdom With Time” featured here, the School of Law professors concluded:

“…the dominant theme of the material taken as a whole or piecemeal does not appeal to the prurient interest—it is not lascivious, it does not excite lustful thoughts, and it hardly creates itching. Under any legal test, we cannot say that the poems are even arguably obscene.”

Finding President Mullins’ stance on the controversy to be frustratingly neutral during end-of-the-year faculty meetings, Kruh began to consider alternative channels for publishing the magazine at the start of the summer. Repeatedly dodging meetings and inquiries from Kruh in the opening months of the new school year, Pomfret and Trammell again hindered the dean’s efforts toward Preview’s publication. Although Kruh had managed to arrange a contract with Conway Printing Co. that promised the independent printing of the controversial poems, the company eventually backed out and suggested having the material cleared by state auditor Jimmy “Red” Jones.

The involvement of state representatives only fueled the strife on campus and in Northwest Arkansas. Some demonstrated their support for Jones and Blake in the Northwest Arkansas Times, praising Jones’s self-declared “Christian-upbringing” and affirming “the integrity and character” of Blake. Meanwhile, students attacked the magazine’s conservative opponents, toting signs that read “Blake Reads Comic Books” and “Send Big Red Jones Back To College” at the October protest. Still more students lambasted University officials for the principle of the conflict. A Student from Little Rock, Bruce Roberts voiced his frustration with the administration by reminding them he “came here to learn new things,” and that “if the university officials know all about filth, [he] should be able to learn about it too.” Senior architecture student Mike Moose wrote a letter to the Traveler’s editor accusing Mullins of having “shirked his responsibility as president” by maintaining neutrality.

University students hold signs in protest of the delayed publication of literary magazine Preview outside of Vol Walker Hall, October 23, 1967. Photo courtesy of Arkansas Traveler Digital Collections.

Despite having found a new partner at Times-Union Printing Company of Little Rock to print the issue off-campus, Jimmie “Red” Jones’s personal opposition to the poems made for slow progress. Over a year and a half had passed since Preview editor Dacus had submitted the work to Blake. Come October of 1967, Dacus was seeking support from the student Senate and attacking the authority of Blake in the Traveler, commenting that “if Mr. Blake were acquainted with contemporary literature, he would not be offended at all.”

After much deliberation, a combined ’66-’67 edition of Preview that featured Mahan’s poems was published through the funding of a “private individual at a commercial printing company.” Although students must have relished in the opportunity to read what had so long been interdicted by the University, the premise of censorship remained unresolved. In October of 1967, reading Mahan’s poems in the newly printed, privately-funded issue of the magazine was a conciliation. This nuance is one to reflect on in conjunction with the disrupted political and social climate of our campus and regional communities as well as of our nation. Statements against racial injustices can be sincere, but they can also be placative. As students we have an opportunity in the upcoming year to hold our institutions accountable for the discrimination and inequities suffered by our peers, to attune our ears to the distinction between words that demand change in words and words that demand change in action.

Sources:

University of Arkansas Digital Collections, Arkansas Traveler Collection. https://digitalcollections.uark.edu/digital/collection/Traveler

University of Arkansas Digital Collections, Razorback Yearbook Collection. https://digitalcollections.uark.edu/digital/collection/Razorbacks

Northwest Arkansas Times, Online Digital Archives. https://www.nwaonline.com/archivesearchnw/