An inside look at a museum archive. Biological Anthropology research and storage room, Division of Anthropology, American Museum of Natural History.

Grace Roberts is pursuing a double major in biology and anthropology and a minor in medical humanities, with an eye towards a career in medicine. For her honors thesis she is studying wear on the teeth of contemporary dental patients in Indianapolis. She expected to find more wear on the teeth of older patients, but that was not the case – “the data was all over the place.” Could there be underlying genetic factors that impact how teeth wear? To answer that question, Grace traveled to the American Museum of Natural History in New York City last January, where she took dental scans from a more genetically unified sample of museum specimens — late-19th/early 20th skulls from Papua New Guinea.

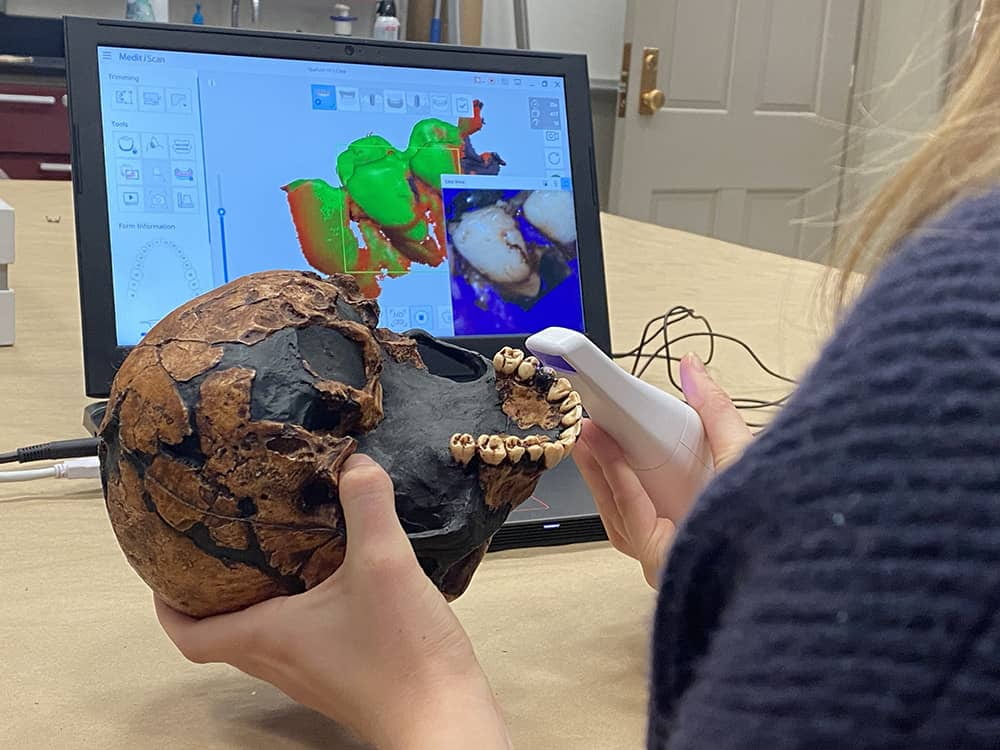

I’m no stranger to research travel, but my trip to New York was easily the most excited I’ve been about my data collection. I visited the American Museum of Natural History to collect dental scans as a part of my ongoing project studying tooth wear in human premolars. My research involves processing three-dimensional scans of premolars to collect quantitative data on their surfaces, which can reveal population-level trends in tooth shape. My previous sample showed a remarkable amount of variation among modern dental patients, so my mentors and I suspect that genetic diversity could be preventing physiological trends across this particular population. To parse this idea out, we decided to compare our original data to those from a more genetically cohesive population: archival specimens collected from Papua New Guinea.

I’ve always wondered what was behind the “staff only” doors scattered throughout museum exhibits, but this was my chance to finally venture through them (whilst struggling to carry the Ungar lab’s dental scanner). Seeing the museum’s biological anthropology collections room for the first time was a bit overwhelming; I’ve likened the space to a multi-story library with what looks like an already shocking number of books that only seems to get bigger the more you sift through them.

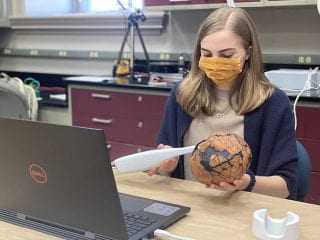

Grace scans a cast of an early Homo sapiens skull. This photo was taken in Dr. Peter Ungar’s lab here on campus. Photo: Hiba Tahir.

Despite being dazzled by the museum environment, I definitely felt the weight of the collections I was working with. Opening a box to find a human skull is not something to be taken lightly, and it’s impossible not to constantly ask yourself “who was this person?” and “how did they end up here?” and “what was their story?” While none of this is known, it’s still a tremendous honor to have worked with these physical pieces of history. Their presence in the museum unfortunately harks back to a largely unethical and disturbing period in anthropology’s beginnings as a discipline (a necessary reality to acknowledge in any anthropology class). Regardless, I’m grateful for the learning this experience provided, and I hope my project can (in some small way) honor the legacies of the individuals who contributed to it.

I finished off my day of data collection with 82 scans, a personal best for the given time frame. The next morning, I returned to sift through the museum’s archives on the samples, hoping to gain information on where these crania were collected, who found them and any other important details. My decision to study classics did not suit me well in this particular circumstance, as I will be spending time in the upcoming months attempting to translate an array of documents in German.

Working in such a renowned and historic museum was more inspiring than I could’ve anticipated and something I will never take for granted. As an anthropology major, this seems like such a critical aspect of my education that I had not yet gained, and there is so much to be learned from being able to interact with samples like this one. The principal benefit of this experience has been an increased appreciation for the role of museum curators as stewards of human history, and it’s easy to forget how much more there is to a museum than the collections on display.

My best advice for researching in archives is to come prepared, in the sense that you anticipate almost anything that could go wrong. I scoured the AMNH online database before my visit attempting to nail down a list of specimens I could use, but this was largely condensed once I got to the museum and was able to see each one in person. You can never be sure how long certain tasks will take to finish, what technological errors could be in store and how much information you’ll be able to gather in a scenario with so many moving parts. Even so, the most important thing I learned is to stay mindful of your environment and the significance of the items you’re working with. It’s easy to get caught up in the technicalities of data collection, especially when it’s as monotonous as mine, but remembering the impact of a particular sample that brought you to it in the first place makes the experience that much more gratifying and meaningful.