The Austro-Hungarian Empire existed from 1867 to 1918 and contained territories that were then integral or partial parts of Austria, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Poland, West Ukraine, Yugoslavia, Romania and Italy. Many highly creative, original and/or gifted persons have been born in such an empire. Examples include: the filmmakers Billy Wilder, Eric Von Stroheim, Otto Preminger, and Fritz Lang; the composer Max Steiner; the writer Franz Kafka; the escape artist Harry Houdini; the actors Peter Lorre and Bela Lugosi; the swimmer and actor Johnny Weissmuller; and the actress and inventor Hedy Lamarr.

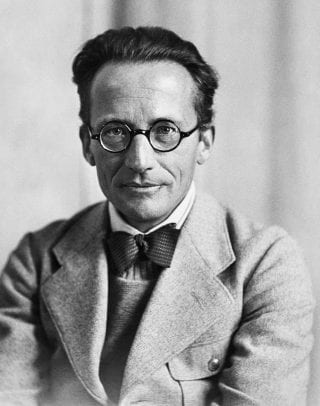

Original Caption: 11/18/1933-The 1933 Nobel Prize in Physics has been awarded jointly to Professor P.H.M. Dirac of Cambridge University, England, and Professor Erwin Schrodinger of Magdalen College, Oxford, England, for having furthered a new and fruitful development of the Atomic Theory. Photo shows Professor Schrodinger.

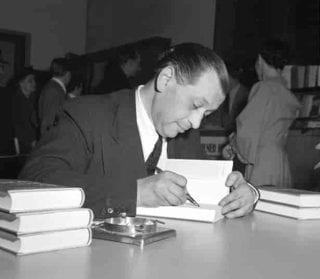

Several Physics Nobel prizes also opened their eyes for the first time in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. A non-exhaustive list of names, citation for their Nobel Prize and year of such prize follows: Erwin Schrödingern “for the discovery of new productive forms of atomic theory” in 1933; Wolfgang Pauli “for the discovery of the Exclusion Principle, also called the Pauli Principle” in 1945; and Eugene Wigner “for his contributions to the theory of the atomic nucleus and the elementary particles, particularly through the discovery and application of fundamental symmetry principles” in 1963. Another physicist, John von Neumann, was also born in Austria-Hungary. He was a child prodigy considered to have been exceptionally bright. For instance, Hans Bethe, the 1967 Physics Nobel prize winner, said about him, “I have sometimes wondered whether a brain like von Neumann’s does not indicate a species superior to that of man,” while the ”father of the atomic bomb” Edward Teller (who was also from Austria-Hungary) stated, “von Neumann would carry on a conversation with my 3-year-old son, and the two of them would talk as equals, and I sometimes wondered if he used the same principle when he talked to the rest of us.” Eugene Wigner further declared, “I have known a great many intelligent people in my life. I knew Max Planck, Max von Laue and Werner Heisenberg. Paul Dirac was my brother-in-law; Leo Szilard and Edward Teller have been among my closest friends; and Albert Einstein was a good friend, too. And I have known many of the brightest younger scientists. But none of them had a mind as quick and acute as Jancsi [John] von Neumann.’’

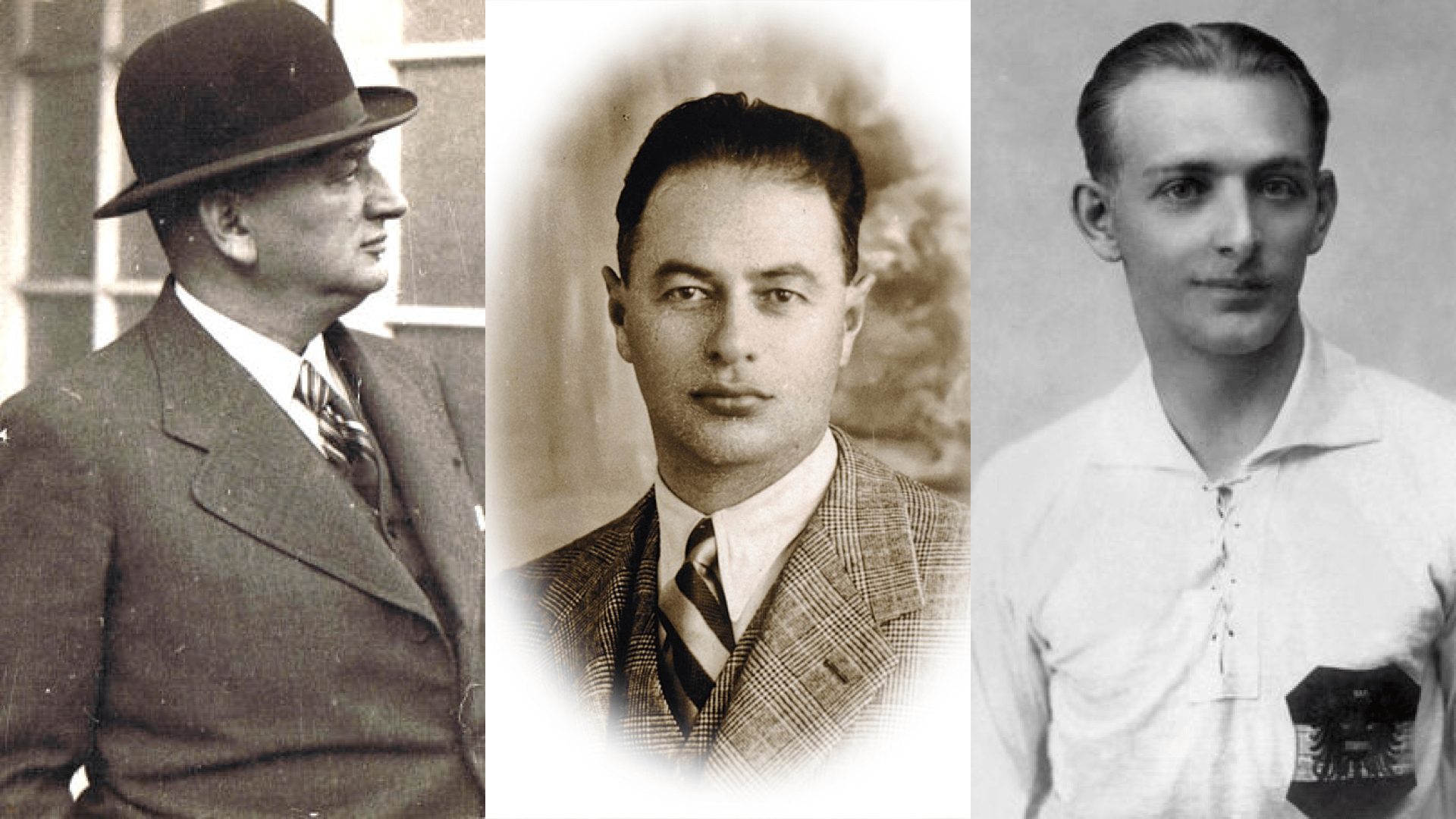

Soccer is by no means exempt to have possessed geniuses, all born during the Austro-Hungarian Empire. For instance, four great coaches and two exceptional players were all from Austria-Hungary. Today, we are going to tell the stories of three of them, with the remaining three discussed in an upcoming article.

The first one is Árpád Weisz who was born on Solt (that now belongs to Hungary) on April 16, 1896. He played soccer for the Hungarian Törekvés SE club in the 1922-23 season, and then for the Jewish team of Maccabi Brno in Czechoslovakia, before moving to Italy in 1924 to join Unione Sportiva Alessandria Calcio 1912 in Piedmont. He stayed there for one year until he transferred to Internazionale in Milan (which is now better known as Inter Milan). Meanwhile, he also wore the Hungarian national team jersey seven times. He was part of the Hungarian squad that participated in the 1924 Olympic games too but was only a substitute for both the 5-0 victory of Poland in the first round and the 3-0 elimination by Egypt in the second round. A knee injury forced him to retire as a player in 1926 at the age of 30. He then embraced a coaching career at Inter, where he called for the first time the 17-year-old Guiseppe Meazza in 1927. This latter will become one of the best Italian players of all time, winner of two World Cups with Italy in 1934 and 1938 and scoring 284 goals in 408 games for Inter Milan between 1927 and 1940 (which makes him the Inter’s all-time top goal scorer). The common stadium of Inter Milan and of the rival AC Milan is officially known as Stadio Guiseppe Meazza since March 2, 1980. With Weisz as the mastermind and Meazza as his arrow on the field with 31 tallies, Inter Milan won its third scudetto in the 1929-30 season, but under the name of Ambrosiana after the patron Saint of Milan and to accommodate the fascist party. Weisz became the youngest coach to win an Italian league title at the age of 34, and remained the coach of Internazionale until 1934, with the exception of the 1931-32 season spent managing Bari in the south of Italy. He moved to coach Novora in 1934 and then Bologna in 1935 where his first two seasons were remarkable as this team from Emilia-Romagna finished first in the 1935-36 and 1936-37 Italian league, despite Meazza scoring 25 goals for Inter in the 1935-36 season and another Italian legend, Silvio Piola (who is the highest all-time goal scorer in Italian top league with 274 goals), having a tally of 21 for Lazio in the 1936-37 Italian championship. At the age of 41, which is rather young for a coach, Árpád Weisz has thus already won three scudetti, one with Inter and two with Bologna where he also mentored another fantastic player, Angelo Schiavo. This latter is the all-time goal scorer of Bologna with 249 goals and was also instrumental for making Italy triumph in the 1934 World Cup by scoring four goals, including the winning goal in the 2-1 victory against Czechoslovakia in extra time during the final. The third, 1937-38 season of Weisz in Bologna was the last one, and the team finished fifth in the league. The main reason for stopping coaching Bologna is that, starting on August 1938, the fascist regime introduced a series of laws against Jews, and Weisz and his family had no choice but to leave Italy, which had become their adopted homeland. The last time Weisz saw Italy was on January 10, 1939, when the train he was in crossed the border with France. After having spent Spring 1939 in Paris, the Weisz family moved to the city of Dordrecht in the Netherlands, where Árpád managed the rather weak local club, Dordrechtsche Football Club (DFC). Árpád Weisz succeeded in bringing that team to the fifth position in their division in the 1939-40 season. However, the German army entered The Netherlands in May 1940, and Árpád Weisz was then prevented from coaching DFC and his children from attending school. The whole family was arrested in 1942 and sent to a concentration camp. His wife Elena, his 12-year-old son, Roberto, and his 8-year-old daughter, Clara, were killed in the gas chambers at Auschwitz three days after they left the Netherlands. Árpád Weisz survived for about a year and a half, due to his strong and healthy constitution, but then died at Auschwitz too on January 31, 1944.

During an Italian Cup game in 2013 between the two teams he made champions, Inter and Bologna, the players arrived with a tee-shirt showing the picture of Weisz, the number 18 (meaning “life” in Hebrew) and the saying,” No racism, for Árpád Weisz.” Moreover, on the 2012 Holocaust Memorial Day, a memorial plaque to honor Weisz was unveiled in Milan’s stadium, called Guiseppe Meazza (also known as San Siro). The great coach (Weisz) and the great player (Meazza) were reunited and are now intertwined for life.

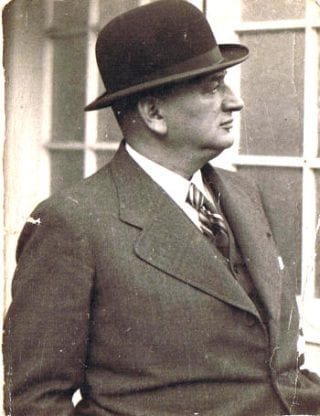

The second prince of Austria-Hungary is Hugo Meisl, who was also born from a Jewish family, like Weisz, but in Bohemia on November 16, 1881. He played for a short period of time for the Vienna Cricket and Football-Club, before becoming a referee. He refereed the first international game between Hungary and England on June 10, 1908, won 7-0 by the Englishmen with a quadruple from a certain George Hilsdon (in this 1908 Hungarian team, there was another Weisz, with the first name Ferenc, who would also die in Auschwitz in 1944). Meisl was a referee for Finland-Italy in the 1912 Olympic Games in Stockholm, Sweden too, for which the Finnish had a 3-2 victory after extra-time in the first round. As we are going to see, it will not be the only time that Meisl would be involved with Italy.

The second prince of Austria-Hungary is Hugo Meisl, who was also born from a Jewish family, like Weisz, but in Bohemia on November 16, 1881. He played for a short period of time for the Vienna Cricket and Football-Club, before becoming a referee. He refereed the first international game between Hungary and England on June 10, 1908, won 7-0 by the Englishmen with a quadruple from a certain George Hilsdon (in this 1908 Hungarian team, there was another Weisz, with the first name Ferenc, who would also die in Auschwitz in 1944). Meisl was a referee for Finland-Italy in the 1912 Olympic Games in Stockholm, Sweden too, for which the Finnish had a 3-2 victory after extra-time in the first round. As we are going to see, it will not be the only time that Meisl would be involved with Italy.

Meisl then turned to coaching and became the manager of the Austrian team in 1912. His first match as national coach was a friendly game against Italy on December 22, 1912, in Genoa, with a 3-1 away victory for the Austrians. Austria was then mostly managed by Heinrich Retschury during World War I when Meisl was a soldier. The track record of Retschury is not particularly brilliant with 6 wins, 4 draws and 13 losses in 23 games. Hugo Meisl then returned as the head coach of Austria in 1919 and would retain such position for 18 years. During his 133 games as manager of the Austria national team, Meisl will count 71 victories, 30 draws and 32 defeats.

Like the story between Weisz and Meazza, a decisive moment in the coaching life of Meisl was meeting an extraordinary player, Matthias Sindelar, who is the third prince of today. He was born in Kozlov, located within the Moravia region (now part of the Czech Republic), on February 10, 1903, in a Catholic family rather than a Jewish one as wrongly written in some articles. Sindelar’s real first name is Matej from Czech origin, that became Matthias once Germanized. At an early age, Sindelar fell in love with the beautiful game, playing on the streets of Vienna where the Sindelar family moved to in 1905. At age 15, Matthias was spotted by a scout from Hertha Vienna and joined this club in 1918 where he stayed for six years. He was then recruited in 1924 by another team from the Austrian capital, Wiener Amateur-SV, who had just won the Austrian championship and Cup. This club then changed its name to the now-better-known Austria Vienna in 1926 because the players became professionals rather than remaining amateurs. Matthias Sindelar was a jewel, with an uncanny gift for dribbling – waltzing over opponents – and for his creativity on the field resulted in him being nicknamed “The Mozart of football.” The theatre critic Alfred Polger remarked on Sindelar, ” “In a way he had brains in his legs, and many remarkable and unexpected things happened to them while they were running.” Another nickname for Sindelar was Der Papierene (“The Paper Man”) but several explanations are usually given for that moniker: 1) his slight built and supposed physical frailty on the pitch, 2) his effortless weave across the field or 3) his ability to escape tough challenges. Considering the exceptional gift of Sindelar for football, it was thus no surprise that Hugo Meisl called him in 1926 to play for the Austrian national team, especially after the Mozart of football had helped Wiener Amateur-SV/Austria Vienna to win the championships in 1926 and the Austrian Cup in 1925 and 1926. The first game of the duo Meisl-Sindelar for Austria was a 2-1 victory over Czechoslovakia in Prague on September 28, 1926, with one goal from Sindelar. The next game was a 7-1 win with two tallies from Sindelar on October 10, 1926. The third game resulted in a 3-1 win against Sweden in Vienna too, with the Paper Man scoring again. However, Meisl was not fully convinced that Sindelar could accept his disciplinarian style, which explains why he only played two games with Austria in 1927, two other matches in 1928, none in 1929 and only one in 1930. And then something important happened in the Ring Café in Vienna in 1931: Meisl was cornered by some football specialists who told him he absolutely had to recall the Paper Man. Sindelar was so popular that it is said fans came to see his games not only to see him play but also to understand how the game should be played. Meisl caved under the pressure and Austria played again with Sindelar on May 16, 1931. It was a 5-0 victory over Scotland, with the Mozart of football making the net shake once in delicious melody. Thanks to the unpredictability and unique artistic vision of Sindelar, combined with the discipline and organization of the other players of the team under the guidance of Meisl, one of the greatest teams in the history of soccer was born that day. It is now known as the Wunderteam and was unbeaten for 14 games in a row. Germany was crushed 5-0 in Vienna on September 14, 1931, with three goals from Sindelar. The 1931-32 Central European International Cup was won for the first and only time by Austria after a 2-2 draw in Hungary, an 8-1 thrashing of Switzerland in Basel, a 2-1 win against Italy in Vienna, a 1-1 draw in Czechoslovakia and a 3-1 victory at home against Switzerland, with Sindelar having a total of four tallies in these games. Meanwhile, the team of Meisl and Sindelar also humiliated Hungary by 8-3 in a friendly game played in Vienna on April 24, 1932, and where Der Papierene scored three times. The series of 14 unbeaten games came to an end in December 1932 in London, when England narrowly defeated the Wunderteam by 4-3 despite another goal from Sindelar. However, this incredible team continued to crush opponents in 1933 and in the first four months of 1934, such as France by 4-0 in Paris, Belgium by 4-1 in Vienna and Bulgaria by 6-1 in Vienna too, with the Mozart of Football scoring once in each of these games. Austria thus entered the 1934 World Cup held in Italy as one clear favorite, especially with a Sindelar now the team captain and having lifted the trophies of the Austrian cup and the Mitrocup (that gathered teams from nations that used to belong to the former Austro-Hungarian empire) with his club of Austria Vienna, both in 1933. Interestingly, the final of this 1933 Mitrocup was between the Austria Vienna-Wiener Amateur-SV of Sindelar and the Ambrosiana-Inter of Meazza and Weisz, with the Italian club winning the first leg 2-1 with one goal form Meazza but the Austrians triumphing in the return leg by 3-1 thanks to a hat-trick from Sindelar and in spite of one goal of Meazza. The two geniuses, Sindelar and Meazza, finished top scorer of this 1933 competition with each five goals in six games (Frantisek Kloz, also born in Austria-Hungary, had a tally of five with Sparta Prague too).

During the 1934 World Cup, the first game against France in Turin was more difficult for Austria than expected with a narrow 3-2 win after extra-time, with one goal from Sindelar. The quarter-final in Bologna against Hungary was also won with difficulty by 2-1. The semi-final against Italy in Milan on June 3, 1934 promised to be Dantesque. However, unfortunate events occurred before and during that game. First, the Swedish referee, Eklind, had dinner with Mussolini the evening before that semi-final. Secondly, the game was played under poor weather conditions, which limited the movement of the ball that Sindelar was so gifted at creating. Thirdly, the tough Luis Monti (who played the previous, 1930 World Cup final with Argentina before switching allegiance to Italy) had a harsh marking of Sindelar. Finally, two protegees of Weisz, Schiavo and Meazza, pushed the Austrian goalkeeper Platzer during the only goal of the game, scored by the Italian Guaita, without the Referee Eklind calling the foul (not so surprisingly, this latter also refereed the final won 2-1 by Italy in Rome in extra-time against Czechoslovakia…). The wonderful team coached by Meisl and with Sindelar on the field was thus out of the final of the 1934 World Cup. Note that Austria, still managed by Meisl but with an amateur team, also lost the final of 1936 Olympic games in Berlin against Italy too: this time by 2-1 in extra time.

How did Meisl and Sinderlar react to the terrible deception of not winning the 1934 World Cup? The Wunderteam drew 2-2 against the vice-champion of the world, Czechoslovakia, in September 1934 and defeated England by 2-1 in 1936. Meanwhile, Sindelar won the 1935 and 1936 Austrian Cups as well as the 1936 Mitropa Cup again with his Vienna club. However, 1937 was a terrible year for the national team of Austria. As a matter of fact, after having coached his last game in Paris against France (for a 2-1 win) on January 24, 1937, Hugo Meisl succumbed to a heart attack less than one month later at the age of 55. Sindelar continued to be briefly part of the Austrian national team, even defeating Italy 2-0 on March 21, 1937, before playing his last official game for Austria on September 19, 1937, for a 4-3 victory against Swizerland, scoring the last of his 26 goals for his country in 43 games. However, The Mozart of football continued to play for his club of Austria Vienna until 1939 for a total of about 600 tallies in about 700 games. In fact, Sinderlar participated in one last, but unofficial, game with his country in April 1938. This was against Germany, just a few weeks after the Anschluss (annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany). It is said that the German officials asked the Austrians not to score any goals end the game with a 0-0 draw to show that the two countries were close brothers. Several accounts indicate that Sindelar defied Nazi Germany 4 times in that game and after. First, he asked his teammates to wear a jersey made with the colors of Austrian flag rather than their traditional shirts. Secondly, he scored one goal during that game, which helped Austria win by 2-0. Third, he celebrated this goal in an extravagant way in front of Nazi officials, likely to show his support for his country and the many Jewish friends he had. Fourth, he refused to play for the unified Germany-Austrian team that, for instance, played in the 1938 World Cup, pretexting he was injured or too old (while he was still showing sparks of brilliance).

Matthias Sindelar, along with his girlfriend Camilla Castagnola (who was not Jewish, as often mistakenly indicated in the literature), were both found dead on January 23, 1939. Three theories exist for these deaths. One states that this was a murder, as a retribution of the Nazi for his opposition to them and to the Anschluss. Another indicates that this was an accident caused by a defective chimney, resulting in carbon monoxide poisoning. The last theory rather suggests suicide and takes its origin in the poem of his friend Friedrich Torberg (also born during the Austrian-Hungary Empire) called ‘’Auf den Tod eines Fußballspielers” (“On the death of a footballer”). The poem reads as follows:

“He was a child of favorites, and his name was Matthias Sindelar. He stood in the middle of a green square because he was a center forward.

He played football and he knew. Besides, not much of life. He lived because he had to live from football game to football game.

He played football like no other. He was full of wit and imagination. He played casually, lightly and cheerfully, he always played, he never fought.

He tossed his blonde head to the side, let his Lord God be kind, and stormed through the green expanse and sometimes right into the gate.

The Hohe Warte rejoiced, the Prater and the stadium, when he fooled his opponent with a smile and quickly ran away from him.

Until one day another opponent suddenly got in his way, a stranger and terribly superior, Before the rule there was no advice.

From a single hard kick. The player Sindelar found himself cast out from the center of the plan because that was the new order.

He stood there for a while, before he left and went home. In a football game, just like in life,

that was the end of the Viennese school.

He was used to combining and combined many a day. His overview allowed him to sense

that his chance lay in the gas tap.

The gate through which he then passed, lay silent and dark entirely. He was a child of favorites and his name was Matthias Sindelar.”

Mystery then remains about the death of the third prince of Austria-Hungary. The Mozart of football received a state funeral with tens of thousands of people lining in the streets of Vienna to say their final goodbye to a football genius. Matthias Sindelar was voted Austrian footballer of the 20th century. He is widely considered as the world’s best player of the 1930’s with Meazza, the two of them having benefited from the advice of Meisl and Weisz, respectively. The Austro-Hungarian Empire has therefore indeed given birth to many extraordinary people. One may thus wonder who the other three princes of Austria-Hungary are. Do you have an idea before the publication of Part II discussing them?

Laurent Bellaiche is a Distinguished Professor in the Physics Department and Institute for Nanoscience and Engineering, as well as the Twenty-First Century Endowed Professor in Optics, Nanoscience and Science Education (for more details, please see: ccmp.uark.edu). His favorite team is Paris Saint-Germain, especially that of the first trophies (French Cups) in the 1980’s, with the three Dominique’s (Baratelli, Bathenay and Rocheteau) and two jewels (Safet Susic and Mustapha Dahleb). His two favorite male football players of all time are Diego Armando Maradona and Robby Rensenbrink. His current three favorite female players are Grace Geyoro, Melchie Dumornay and, of course, Sophia Smith. His favorite soccer/football quote is one from Bill Shankly, “Some people think football is a matter of life and death – I assure you, it’s much more important than that.”