Jamie Zakovec, ’22, B.I.D., magna cum laude, graduated last May and now works as an interior designer at Modus Studio. Her honors capstone project, which assessed the acoustic and spatial interior environments of auditoriums across campus, was the basis for a proposal that was awarded a grant by the Women’s Giving Circle, ensuring that work to improve accessibility in our learning spaces will continue.

1. How and why did you get involved in researching acoustical conditions on the U of A campus?

My older brother is completely deaf and has two cochlear implants. If you’re just talking to him normally you wouldn’t be able to tell, but in group settings, anything bigger than 15 or 20 people, the cochlear implants can’t distinguish important cues that are needed to separate speech from background noise. For instance, if he’s in a lecture hall like the ones when he attended the U of A, sound bounces everywhere, and it could be hard for him to distinguish what the professor at the front is saying. He has expressed frustrations to me when we are in large group settings and it is hard for him to understand what people are saying. Going into interior design, I started realizing through taking my generals in those giant lecture halls that it isn’t the best setup for students who are hard of hearing, people who are neurodiverse, or even just easily distracted. An extensive amount of noise is going around these auditoriums, let alone background noise like HVAC and mechanical equipment. I also started wondering how many students here have hearing loss and don’t want to tell anybody. We have an estimated 377 students who are registered with hearing loss, but how many aren’t or just do not realize that they do?

That’s where I was sparked with the inspiration for the research, but I think it grew into something bigger than that. I started looking not just at students with hearing loss, but also students who have trouble paying attention or maybe their second language is English and it’s hard for them to understand, and they don’t want to sit at the very front of the classroom without their friends just so they can understand the class.

2. What did your research for the capstone suggest about the current learning environment in auditoriums on campus?

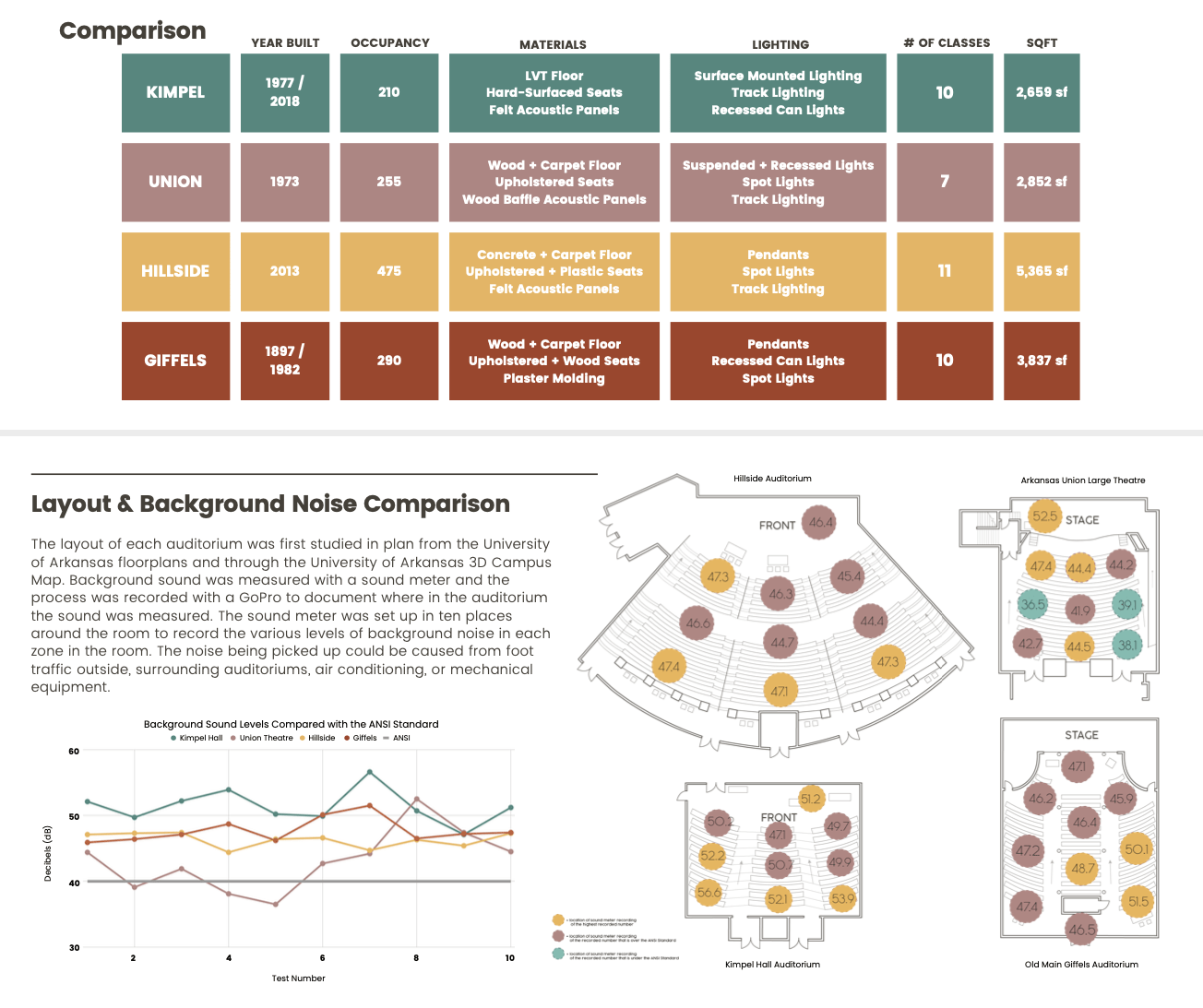

I studied four specific auditoriums: Kimpel, Giffels (which is the oldest auditorium on campus), the Union Theatre and Hillside. I picked a wide range of seating capacities, ages of the auditorium and places where different classes are held just because everyone’s generals look different based on their major. I studied all of them by measuring the acoustics without any students in them, just based on people walking by, the HVAC turning on and any other mechanical equipment that was making noises–that was the only noise that picked up between classes and during classes.

Based on the acoustical standards I measured, none of the auditoriums met the requirements for the Acoustical Society of America and the American National Standards Institute (ANSI), which is unacceptable, considering some of them were built only a couple years ago, versus the ones that were built 50+ years ago. I realized that we need to make both physical changes to auditoriums, but more importantly, improve their technology and make sure professors are aware of that. We need to make sure they wear microphones because in almost all my generals, most professors wouldn’t wear mics because people think because there’s only 50 people in the class, everyone should be able to hear. If a student who does have hearing loss doesn’t know to go walk up and tell the professor, they might just sit there all semester, or just stop coming to class.

Learning through my research how bad the acoustics already were made me realize we need to bring the issue to the university’s attention. When we looked at the ADA standards that the University puts out every couple of years–I think this was the 2016 version–they didn’t have any sections regarding acoustics or have any documentation for testing for each auditorium. I looked at other ADA standards, which are more focused around visible disability, and just started to notice what needs to be corrected. Looking at acoustics is usually the last thought and it’s generally considered that putting up acoustic panels on walls will fix it.

3. How does architectural space and building design impact communication for both students and faculty?

A big thing with people who have hearing loss is lip-reading. My brother, when he can’t understand things, he’ll start reading lips. And based on the layouts of the auditoriums you are sitting with your backs to each other, so if somebody asks a question, you can’t understand what that person said. And if the professor doesn’t repeat the question, they can completely miss what’s being talked about.

I think looking at auditoriums and that traditional layout, which works in some ways to amplify sound, it also doesn’t work for students who need that kind of communication. Maybe having more seating available on the sides where you can see the professor and still look at students. Or, if we are thinking more abstractly, looking at whether auditoriums are the best way to teach to a large group of students, or if using spaces providing more group-based seating to encourage communication between students. These are just some of the options we considered studying, but realize it might not be the most effective for the university’s auditoriums as a whole.

In looking at those different seating possibilities for auditoriums spatially, I also researched technology for teachers so we can bring students closer to them. If a professor has hearing loss, how can they hear students? And that’s actually more of the age group we’re looking at with hearing loss, because as you get older, your hearing goes. This next stage of research is where we are going to look at how we can make these spaces more accessible for students and professors and look more at the interaction and experiences of people in the auditoriums more than just the space itself.

The research on spatial layouts was for exploring different types of accessible seating for large groups, but for the outcomes for my research, the goal is to provide an obtainable set of solutions that the University can use to assist in the accessibility for students and faculty with hearing loss. This looks like it will be more through technology and creating a set of standards for faculty to implement.

Jamie Zakovec (right) with Jennifer Webb (left), associate professor of interior design, and Rachel Glade (center), director of communication sciences and disorders, who were co-principal investigators on the Women’s Giving Circle Grant.

4. Can you speak a bit about the principles of universal design? How does everyone stand to benefit from implementing these changes to the acoustics?

I grew up being aware of hearing loss and cochlear implants so I was more mindful of the need for improvements. Most people who have a similar experience with someone in their lives, or themselves, are aware of those unmet needs, but we still need to bring awareness to people who might not be conscious of how difficult it can be for someone needing assistance and it not being available. Everyone can go through changes in life and anybody’s ability may change at any point. So even if you’re thinking “I have decent eyesight, I have good hearing, I can walk,” that could change. By making everything accessible you are giving equal opportunity to each student, each faculty member, every person using the university’s campus. And that encourages everybody’s ability to learn and gain knowledge and hear other people’s ideas.

I think what we want moving forward in society is the sharing of ideas and the ability to understand where people are coming from. Providing equal opportunity so people won’t feel nervous walking into a place because they’re going to have to ask for help or get special services is going to benefit everyone.

5. How does your current work at Modus Studio relate to the research done for your honors capstone project?

As architecture students, we’re taught to push the limits, the boundaries of design and creativity, which is important and we need to do that. I think once I got into the field, especially learning more about ADA and ANSI and just how detailed and complicated it is, it became about trying to incorporate it into designs. And honestly, even though I’ve spent years studying it, it can be frustrating trying to incorporate certain things into your design that you have spent months, sometimes years, trying to cultivate.

It’s taken a lot for me to realize accessibility isn’t that simple. It can cost a lot of money, and it costs a lot of time and effort. I think what I’ve learned is that accessibility has to be thought of as a main idea, which is hard, because you just want to focus on making the project look extraordinary. But people from any background need to be able to use a space. I think bringing that awareness to the design community, and also to educational communities is important. We need to start thinking about it from the beginning of a design rather than at the end.

Note:

Jennifer Webb, associate professor of interior design, and Rachel Glade, director of communication sciences and disorders and honors program director for the College of Education and Health Professions, were co-principal investigators on the Women’s Giving Circle Grant. They will continue work on this project with other students in their programs moving forward.