by Swikar Pyakurel and Suyash Rijal

Sir Ralph Turner, a British philologist, and professor of Indian Linguistics who also served with the Gurkha Rifles in the British Army during World War I, famously praised his Gurkha comrades as “stubborn and indomitable peasants” who “endured hunger and thirst and wounds” in battle without complaint. He declared them to be the “bravest of the brave, most generous of the generous,” and asserted that no country had more faithful friends than the Gurkhas. Indian Army Chief Field Marshal Sam Manekshaw, also heaped praise on his fellow Gurkhas, describing their valor: “If a man says he is not afraid of dying, he is either lying or is a Gurkha.”

The Royal Gurkha Rifles regiment in the British Army lives by the motto, “Better to die than to be a coward,” which rightfully encompassesg their spirit of bravery. Well, these Gurkhas seem to be brave, but what does Nepal have to do with Gurkhas, and what on earth does that have to do with football?

“Gurkha” is the anglicized form of the Nepali word “Gorkha,” and has its roots in the Kingdom of Gorkha, one of the many small kingdoms that comprised present-day Nepal. Some 300 years ago, Prithvi Narayan Shah, an ambitious king from Gorkha, envisioned the unification of the small nations in the Himalayan foothills. He and his army successfully achieved most of that goal of unifying numerous small kingdoms into a larger entity later named Nepal. Later on, during the height of the British Empire, British troops from the British Raj (the British East India Company’s occupation of India was also called the British Raj) attempted to invade unified Nepal. On paper, The British were well-armed with modern guns and ammunition, The battlefield told a different story as they were defeated by Nepali forces armed with Khukuri knives and their unconventional guerilla warfare tactics such as hurling stones and rolling logs down the mountains. The battle lasted for over six months culminating in the Treaty of Sugauli to end the war. Amazed by their display of valor, the British decided to befriend the Gorkhali and created a brigade in their army dedicated to enlisting Nepali warriors. Those Nepali warriors were heroic for the British in several wars around the world such as in Myanmar and Falkland Islands and went on to gain fame as the Gurkhas for their valor in battle.

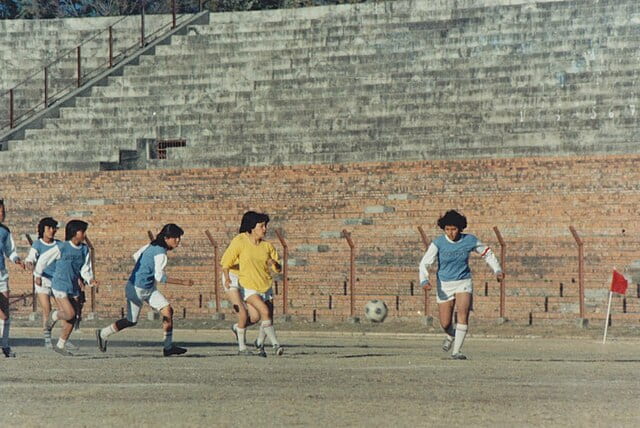

The term Gurkha is not limited to describing only the fearless warriors from the then kingdom of Gorkha, though. It doesn’t even solely define the Nepali population; rather, it collectively encompasses the entire Nepali diaspora, and the Nepali-speaking people take pride in being described as ‘Gorkhali’ or ‘Gorkhe’ or ‘Gurkha.’ When people think about Nepal, they typically associate it with the majestic Himalayan peaks rising kilometers high above sea level, the insanely fit and mountain-adapted Sherpas essential for almost every mountain expedition, the birthplace of Siddhartha Gautam who later became Lord Buddha, poverty, the Gurkhas and may be a ton of other things. Football, however, doesn’t make it into their wildest imaginations.

These people can’t be blamed, though, as Nepali football teams haven’t achieved anything remarkable at the international level. The Nepali men’s team is ranked 175 out of 207 ranked nations, and the women’s team is ranked 101 out of 186 ranked nations. But why are these people, who are praised for their performance in battle and mountaineering, not excelling at football? Are they not fit for football? Does it take different genetics to perform in football compared to battles and mountaineering? Are there even any Nepali who have managed to play in the elite European football leagues?

It turns out a few Nepali individuals (including those of Nepali origin) have managed to play for elite European teams. Bimal Gharti Magar is one such Nepali player, perhaps the first one, who had a taste of European football, although not for a senior team. Born in Nepal, he was selected by the All Nepal Football Association (ANFA), the main governing body for Nepali football, to join their academy after they recognized his talent at a young age. Playing as a forward, je went on to become the youngest Nepali player to be capped for the senior National team at the age of 15 when he played against Bangladesh in an international friendly match.

In 2013, Magar underwent trials for the under-16 (U-16) team of FC Twente, a club based in the Dutch city of Enschede that regularly features in the Eredivisie, the highest division of Dutch football where they were crowned champions in the 2009-10 season. Although impressive in the trials, scoring a few goals in a friendly appearance for FC Twente U-16,Magar unfortunately could not continue with the club due to FIFA transfer and employment rules for young players. In 2014, he had a successful trial at RSC Anderlecht, a Belgian top-flight club, and earned a one-year contract to join their U-19 team. Following his term at Anderlecht, he briefly joined K.R.C. Genk U-19 academy. Since then, he has played for several local Nepali clubs and as of 2023, represented Nepal’s National men’s team a total of 42 times.

Perhaps the most remarkable player is Asmita Ale, a British citizen and the daughter of a British Gurkha soldier. She professionally plays as a left-back for the senior women’s team of Tottenham Hotspur Football Club in London. Ale’s youth career started at the tender age of eight whenshe was signed by the famed Aston Villa academy who recognized her early career skills and potential. The Birmingham-based team were not disappointed as she progressed through their ranks and earned her first professional contract at 18.

Ale’s rapid rise as a footballer saw her voted as the best player in the squad by her Aston Villa teammates in the 2019 Women’s Super League (WSL) season. Known for her tenacious defending, she managed an impressive 79 pass interceptions, the highest in the WSL that season. Alehas also represented England several times andhas been selected to play for the U-16, U-19, and U-23 English women’s teams and is considered one of the rising stars for the young Lionesses.

Kiban Rai is another player of Nepali descent who plays in England’s Newport County A.F.C., a club that finished fifteenth among the twenty-four participating clubs in English Football League Two last season. The EFL two is the third-highest division in the English Football League and the fourth-highest division in the overall English football league system. Rai is a Welsh national born to Nepali parents whose father was also a British Gurkha. He joined Newport County’s youth academy at the U-15 level and secured his professional contract in 2023. He plays forward and attacking midfielder positions for his team. He is the first male of Nepali descent to play in the EFL and also the first male of Nepali origin to score against an English Premier League side. In a recent EFL Cup (also called Carabao Cup) game he scored a last-minute goal against Brentford, a team currently standing thirteenth in the English Premier League, although his team lost in the penalty shootouts in that match.

With the aforementioned examples in mind, it appears that the Nepali are not exclusively destined for feats in combat and mountaineering. Although few, individuals from Nepal and of Nepali origin too have managed to play for European teams and have performed well. Several others have gone on to play in more competitive leagues than the local Nepali ones, such as those in the Philippines, Malaysia, Australia, Israel, etc., and have excelled.

The fact remains that, unfortunately, Nepal is a developing country facing economic struggles, and sports are given one of the lowest priorities by Nepali authorities due to economic conditions. Most Nepali players train and play with minimal resources in local leagues where competition is not of the highest level, hindering the development of their skills. Furthermore, the instability of Nepal’s football governing body which is constantly associated with corruption, impedes progress in football. These systematic failures by the authorities mean that an economically viable career as a footballer in Nepal is a pipe dream. Such vulnerability in the players’ mindset is evident in the recent exodus of professional footballers to Australia and other foreign countries in hopes of a better career. In a society plagued by economic struggles, parents are not willing to incentivize and encourage their kids to be footballers with no career prospects, thus depriving an entire generation of future footballers of encouragement and resources early on in their development. Nevertheless, the people of Nepal are second to none in their love for this beautiful game. One can find individuals in the remote corners of Nepal donning jerseys (often replicas!) of their favorite teams, passionately supporting them. The aforementioned footballers in European football infrastructure have shown that with the right recipe of training, facilities, and economic incentives, aspiring footballers from Nepal too could shine on the world stage and Genetics is not the issue!

Swikar Pyakurel is currently pursuing Masters of Science in Civil Engineering at UARK. He is originally from Nepal as well. Outside of playing soccer and following Chelsea FC, the team known as The Pride of London, Swikar is big into exploring the outdoors and has explored miles of the Arkansas Ozarks.

Suyash Rijal is a graduate student in physics at UARK. He is from Nepal and he loves to play and watch soccer. Suyash is a supporter of Manchester United football club who, unfortunately, have not been doing well in the past decade. He loves iconic Man United stories such as those of Matt Busby, Alex Ferguson, and the class of 92. His Christmas wish for 2023 is that the proposed sale of Manchester United football club becomes successful.