Joshua Jacobs is a fourth-year Bodenhamer Fellow studying international and global studies with minors in classical, Jewish, and religious studies. He studied abroad in Greece this summer, touring 33 archaeological sites and 19 museums in 18 days. Joshua researched ancient funerary customs around the country and documented his experience, which affirmed to him the benefits of learning history hands-on.

This summer, I had the opportunity to spend three weeks traveling around Greece studying funerary customs throughout the various stages of civilization in the country (e.g., ancient Greek city-states, Byzantine Christianity, Turkish occupation, etc.). Given that my honors thesis explores death and the afterlife in the world of ancient Israel, Dr. Daniel Levine, who directed this program, suggested that this trip would provide excellent comparative material. Over the course of 18 days, our group visited 33 archaeological sites, some of which are not yet published, and 19 museums. Moreover, our excursions were not limited to one location: We had the opportunity to explore Athens, Boeotia, Euboea, the Argolid, Attica and Crete.

This summer, I had the opportunity to spend three weeks traveling around Greece studying funerary customs throughout the various stages of civilization in the country (e.g., ancient Greek city-states, Byzantine Christianity, Turkish occupation, etc.). Given that my honors thesis explores death and the afterlife in the world of ancient Israel, Dr. Daniel Levine, who directed this program, suggested that this trip would provide excellent comparative material. Over the course of 18 days, our group visited 33 archaeological sites, some of which are not yet published, and 19 museums. Moreover, our excursions were not limited to one location: We had the opportunity to explore Athens, Boeotia, Euboea, the Argolid, Attica and Crete.

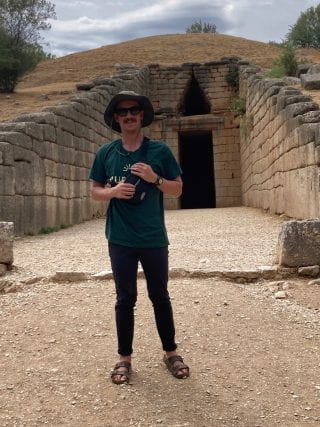

For many of our site visits, we were led by exceptional scholars. For others, it was the responsibility of one student in our group to conduct a site report, instructing the others about the history and significance of sites like the Minoan chamber tombs in Armenoi, the Soros tomb of the Athenian dead from Marathon, and the so-called “Treasury of Atreus,” a monumental Mycenaean tholos tomb. My site report was on a Roman-era cemetery in Kenchreai, a port of ancient Corinth. The cemetery was a mixture of monumental chamber tombs and smaller cist graves. It appears that this cemetery was composed of a mixed population. During our visit to the site, we were able to descend into the chamber tombs and view elegant wall paintings and the places where the dead were buried. The idea of a chamber tomb was one that our group encountered across millennia and hundreds of miles. The Minoan chamber tombs in Armenoi, mentioned above, represent an example from the early third millennium BCE, constructed by a civilization mixed with Mycenean influences. The Soros tomb, on the other hand, was a huge dirt mound, which was probably cost-effective to bury hundreds of soldiers. Perhaps most magnificent of all the tombs we visited, the misnamed “Treasury of Atreus” was built with bricks that went up to my waist. This tomb, not a treasury at all, was dozens of feet tall, and its entrance was covered with dirt after its use, meaning it was not meant to be seen.

Getting Hands-on with the Past and Present

This trip was one of tangible learning; it was not uncommon for the group to sit among the rubble of some ancient place in the late afternoon as we listened to lectures on its past glory. It is difficult to describe exactly how this trip expanded the horizons of my studies in Greece. Suffice it to say, reading ancient texts in an air-conditioned classroom in the United States can only provide part of the real image that made up the world of ancient Greece. The focus of the trip being death, we began our studies with a reading of William Cullen Bryant’s 1821 poem “Thanatopsis.” In this work, the author writes, “All that tread / The globe are but a handful to the tribes / That slumber in its bosom.” This striking statement echoed numerous times through my head as we looked upon the skeletons of people who would have divided themselves in life, but who now look all too similar.

Despite the goal of our study, our group was incredibly vivacious, and we had many an opportunity to interact with Greece as it is in the modern world. One particular experience, near the beginning of our travels outside of Athens, has cemented itself warmly in my memory of the trip. While riding on the bus, driven by a middle-aged Greek man named Christos, Dr. Levine began to teach us a song called “Otan Tha Pao…,” in English, “When I go…” The song is similar in essence to the American song, “Old MacDonald.” Children all over Greece are taught this song at a young age, and it is known by almost everyone. After Dr. Levine had given us a tutorial on how to sing this Greek children’s song, our beloved Christos asked for the microphone, and we were serenaded by the voice of a man, essentially a stranger, who grew up with this very song. This cemented a lovely relationship with Christos, who hauled us around Greece for nine days.

Although there are not many students of the classics at the University of Arkansas, I would highly recommend this program and others like it to any student whose research or interests leads them naturally to spend hours delving deeply into texts. I consider myself a philologist in training, but there is nothing better to round out one’s knowledge of a particular region or time period like going to visit that same place.

Returning home, I am equipped with numerous pages of bibliography and a firm grasp on various funerary and mortuary customs practiced throughout Greek history, as well as face-to-face interaction with related monuments and archaeological sites. Something else I learned while on this trip is that it is all too easy while conducting research to focus on one particular, and ever smaller, area of study. While abroad, I decided that when I got home, I would spend time just reading entire works, in English, to gain breadth of knowledge. Authors like Herodotus, Thucydides, and texts like the Epic of Gilgamesh and Enuma Elish will contribute greatly to my general knowledge of the ancient Near East and Mediterranean.