Terrell Page is an Honors College Fellow from Magnolia, AR, studying English education. He recently presented on his honors thesis at the Serious Play Conference on game-based learning in Toronto, Canada, as the only undergraduate speaker. Here, he recounted the educational outcomes of teaching collaborative worldbuilding in a local high school creative writing class to show students how videogames tell stories.

1. Can you say a little bit about the research that you presented on collaborative worldbuilding?

I presented on the work I had done for my honors thesis last year teaching in a high school class. At first, I had tried to teach a unit on critically analyzing the game Undertale and pairing it with the book, The Wizard of Oz. I saw some similar themes (like trying to get back home), and the characters are similar. But that would have taken eight weeks, and we were told we had three. And Chromebooks can’t even download the game, either. So, I had to backtrack and see what videogames and books have in common at the surface level. What do they both do? And this was a creative writing class, not an English language arts class. So, we had to come up with something that the students would write. I found this book, Collaborative Worldbuilding for Writers and Gamers by Dr. Trent Hergenrader. And it turns out, he uses all of that. I pretty much pulled from his book and then modified it to suit whatever we needed.

This was for a creative writing class at Fayetteville High School. It blew my mind that they have a creative writing class in high school. The teacher, Amy Matthews, was the only teacher who spoke up like, “Yeah, okay. You’re doing something with videogames and writing? Sure, I’ll help.” Because I had asked the entire school and–maybe it’s this systemic thing that usually English teachers don’t know very much about games. I don’t know. At least, that’s what I ran into as a kid, and I ran into it again as an adult. But Mrs. Matthews did know about games. She plays the precursors to digital role-playing games: tabletop role-playing games, like Dungeons & Dragons. She had started a club and everything, so I had to learn about D&D and realize that some of what they were doing is also collaborative worldbuilding. The students already had a lot of experience with that.

The goal was to influence how the students think about creative writing. The students were in groups of five or four by genre and they designed a fictional world together. Each individual wrote a short story about a character in that world. The stories weren’t the same because their characters took different paths. The students overall, said that they learned that it’s important to know your world, your setting really, really well, even if you don’t tell all the details to the reader. That makes things more believable. And that was the end goal, they know how to solidify their setting in writing. I think it worked a lot.

2. What benefits do you see to game-based learning?

This is the benefit that everybody usually quotes–that the students who usually aren’t paying attention start paying attention because you brought up games. But taking it a step further, if the teacher actually knows how to implement the game or game design then the whole class can benefit. They start to realize that writing elements like theme, character, plot are not just in books, but everywhere.

Many times you’ll have a teacher who tries to jump on the game-based learning bandwagon and the students who normally don’t pay attention in class perk up. But then the teacher can ruin it if they don’t know anything about games. And so the students who weren’t paying attention are now paying even less attention than before. So if you actually know how to implement it, then everybody jumps up in comprehension.

What I learned was that you have to know your students–know what genres they’re interested in. Before I started my unit I sent an opening a survey about what their favorite genres were. What helped was me knowing about games in general and reading things like Game Informer. For instance, one group decided that they wanted their world to have crafting, and I had never played Minecraft at this point. So when I did individualized group conferences, I told them I would give myself homework: I’m going to go play Minecraft and then I’ll come back to you. And I did exactly that because the Student Technology Center at the U of A had a demo of Minecraft. I came back knowing the intricacies, what it felt like to try to survive a day in Minecraft. It’s just different when you have actually played the games.

3. What was your experience at the Serious Play Conference like?

Great. I had been dying to have a place where game-based education was the whole conference instead of just an education conference where game-based learning is a small little corner in the action. When I found this conference, I realized the U.S. can’t have this kind of conference, we’re not ready for that. Game-based learning, just mentioning using a game in the classroom is kind of controversial in the United States, because it’s play. But in Canada, no, not at all. Which is interesting, because at the conference they were mentioning all these things that would be a very, very difficult thing to try to do in the United States. Some of the games there were city builder games talking about climate change, or a visual novel about a refugee’s journey from the Middle East to Europe. I was thinking, “I wish that we had, but it’s not going to work here.”

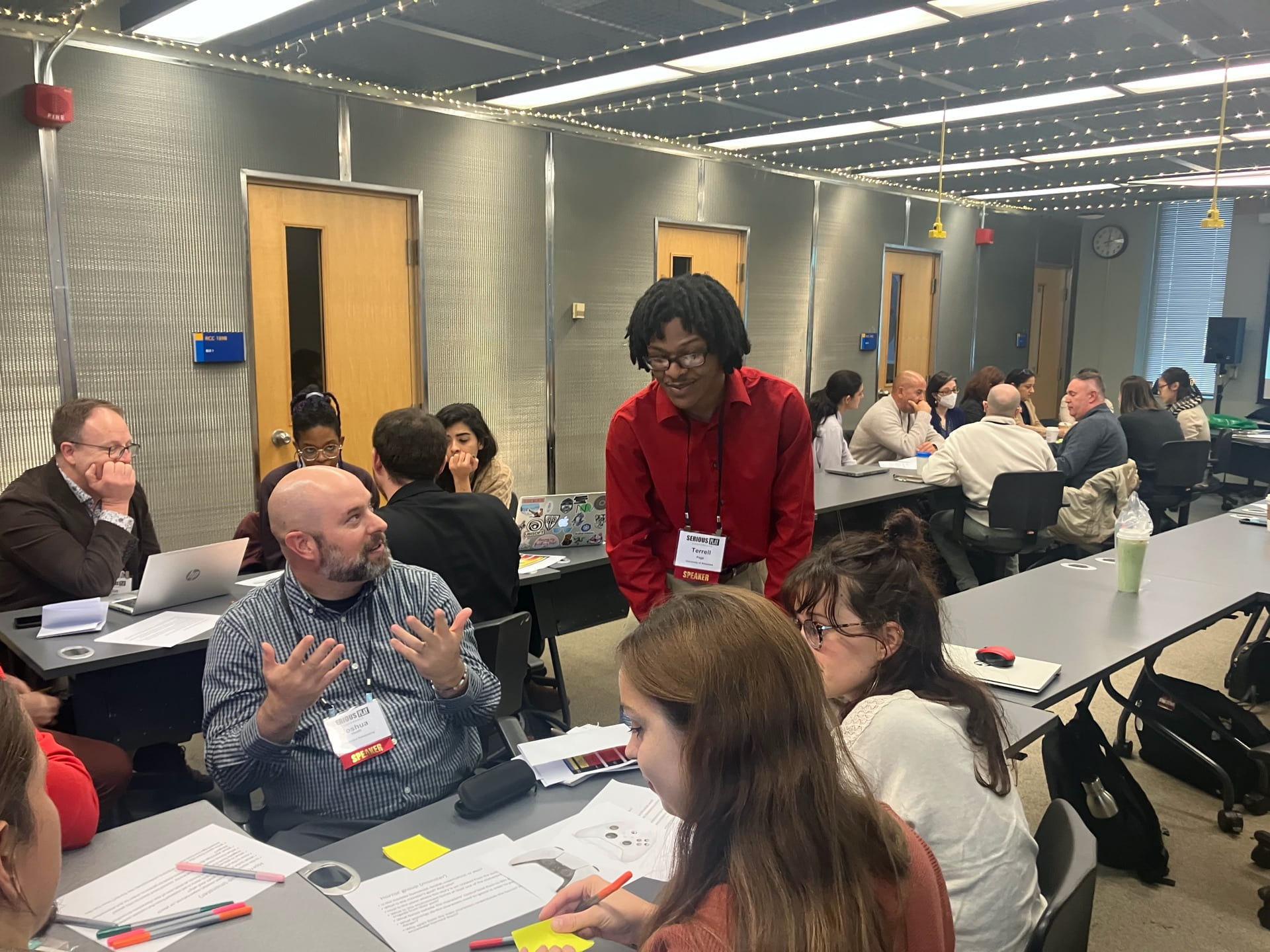

When giving my presentation, I talked about a few slides. But then I handed out a bunch of giant pieces of paper, sticky notes, and pencils, and we all did a mini version of what I put the students through in class. And the participants all woke up. After the conference, some attendees came up and told me that they’d gone to this conference for years but had never seen anything like that. I thought that was surprising for a conference on game-based education–I certainly wasn’t the only presenter who did anything interactive, after all. Maybe I was the only one who made the participants use colored pencils and sticky notes, or something. In fact, there were about 100-and-something speakers, but out of all of them, I was one of two to be featured on Tabletop News (a news network for tabletop games).

4. Do you have advice to other students that would be interested in like attending a conference?

With the parameters of the honors college grant, I thought that the only way I could go to Canada to attend this conference was if I was a speaker, because the wording sounded like it was about presenting. But this wasn’t that kind of conference where every attendee who’s there sets up a board: I had to apply to be a speaker. My advisor, professor David Fredrick, was very confident that I would get in with this project. And when I went to look at the conference page and scroll down the list, I realize the other presenters are people in the middle of their careers, and then there’s me, an undergrad, grinning. And apparently, this year, they had the most graduate students they’ve ever had present. So they made a whole section for grad students and then they plopped me in that section. So I was with all the grad students just not telling anybody that I was an undergrad. Of course, they found out anyway.

One thing I would tell students is that if you find a conference that you need to go to, just apply. It may take a couple of tries, it might not. But just go for it. Hopefully your mentor believes in you, like mine did. But apply. You could probably get a speaking position, even if you see that most of the speakers are nowhere near your age. And they’ll be pleasantly surprised to meet you. I don’t know what’s like in other fields, but they were happy to see me at the conference.

5. Did participating in the conference impact your research interests?

What it did was it emboldened me, it made me feel like my research is actually needed. Because once I realized that game-based education’s stigma in the United States doesn’t exist elsewhere it made me realize how I can pitch my thesis: that collaborative worldbuilding is something you can do when you don’t have access to videogames in the classroom. You can do collaborative worldbuilding when you don’t have the financial resources, the technological resources—because Chromebooks can’t download most games—or when you don’t have the political leeway to do so. So instead you can say, “hey, it’s a creative writing thing. It’s worldbuilding.” That’s technically a book thing. And we’re doing collaboration, which is what most teaching education discourse is going towards–having students work together—and it’s got that in the name. Maybe we can get away with it.