Niala Gotel is an English major in the Northwest Arkansas Community College Honors program. Originally from Ontario and with Caribbean roots, she is an avid observer of people, and is always struck by the diversity of the Northwest Arkansas region. Her interest in people’s responses to the COVID-19 pandemic has led to ongoing research projects to explore the relationship between work and its effect on the human condition.

I’m unapologetically a child of the 80s. My memories are as vivid as the cartoons I watched on Saturday mornings. But in the current COVID-19 pandemic, my memories are showing me just how much my worldview was shaped by the media that I consumed along with my cereal. In our consumerist society, I’ve had no shortage of options, but when it comes to the way I see certain people, the media has controlled my choices.

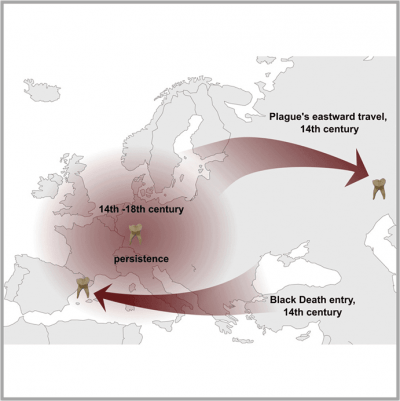

New evidence on the spread of the Black Death has emerged, based on DNA evidence recovered from dental pulp found in medieval burial sites.

Media controls the narrative in our societies, and it’s been that way for centuries. One of the earliest recorded cases of propaganda dates to 515 BC in Iran. The Behistun Inscription, a large relief carved into the side of Mount Behistun, details the victories and accomplishments of King Darius I and established his divine right to rule. Its strategic placement and appeal to the ideologies of his time ensured that travelers as well as his own people would view him with fear as well as admiration.

This appeal to emotion while maintaining credibility are a few of the touchstones of successful propaganda. In her Pandemic lecture on Medieval Apocalypse, Honors College Dean Lynda Coon points out that until recently, the prevailing thought was that plagues appeared in the East and infected the West, but new evidence shows that plague originated with infected grain and livestock in Europe and was shipped to the East. Because the cause of the disease was unknown, it contributed to Western discrimination and distrust of the East.

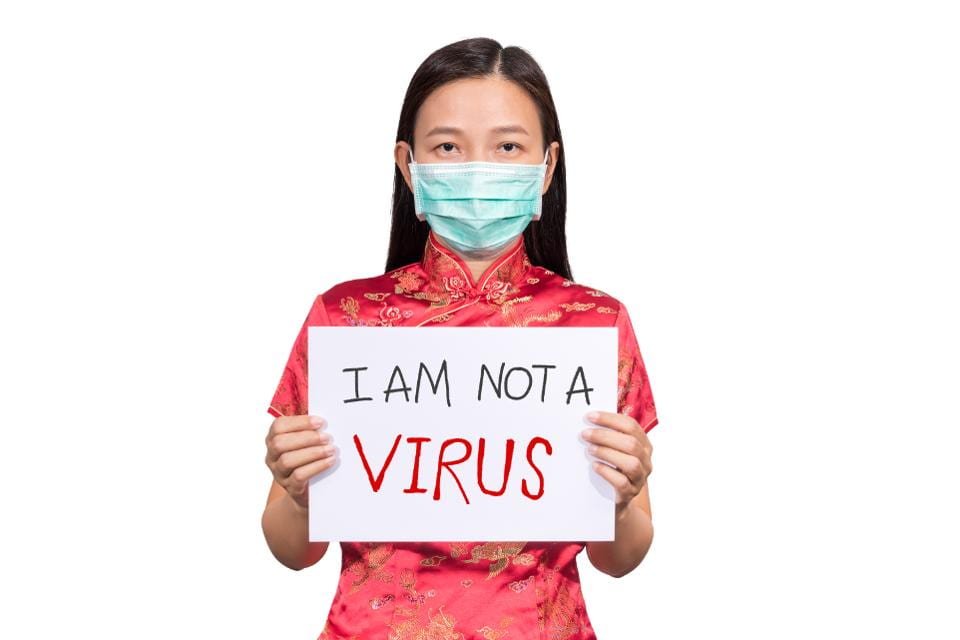

Despite the findings of current research, can anything eliminate the xenophobia that is now an undeniable part of our Western identity? Stereotypes about bad drivers, casual references in standup comedy, or Kung-Fu movies, where the American must defeat the evil Asian opponent at all costs, are all rooted in fear, but taken for granted. The anti-Asia sentiment is palpable.

In the past few decades, distrust of Asian cultures has been exacerbated by policies of the Chinese Communist regime and military actions by the Japanese, Vietnamese and North Koreans, among others. The fear of Asian governments extends to Asian people in general, so it shouldn’t be surprising that during the current pandemic, President Trump’s term “Chinese virus” was met with acceptance from so many. While some braced against the term and denounced it as divisive and racist, others in power repeated it.

Presenting the virus as foreign can be seen as a deliberate move on the part of the President to maintain the divide between the East and West. It’s easier to maintain the idea that China is part of the “other”; the cause of the problem rather than part of the solution, even though they responded quickly to the pandemic. My friend Judy Wong, a Canadian financial analyst and author based in Hong Kong, told me, “It could have been an opportunity to come together, and treat this thing together like a human problem; us versus nature and let’s solve it together. But that just isn’t what happened.”

But it’s the Chinese collectivist culture, the very thing that the West finds so unsettling, that may hold the key to containing the coronavirus. Holistic thinking, sacrificing individual liberties and rights for the benefit of the whole translate to mandatory masks, social distancing and collaborative development of new technology. Westerners struggle with the idea of mandatory isolation, but at what cost? Surely the solution to a global pandemic lies outside the realm of outdated, xenophobic ideology. It’s time we find out where East blends with West so we can benefit from the best of both.