Meg McCartney is a fourth-year honors student from Fayetteville, AR, majoring in studio art with a concentration in sculpture and experimental media. Meg’s thesis project is a video game titled Red Moss that offers players an interactive narrative experience within the fictional small town of Larking, Arkansas. Through the game, Meg hopes to paint a nuanced picture of the contemporary American South.

1. How and why did you get involved with video game design?

1. How and why did you get involved with video game design?

I’ve always played video games and I’ve always done art, but I didn’t really know what I wanted to do. I applied as a biology major to the U of A, as I feel like most people do–apply as a science major—but I switched over to art because it felt like a major I would have fun completing. But then I couldn’t really find anything within the fine arts that I wanted to do. Both my parents have fine arts degrees and I had them telling me not to do fine arts, but my dad’s in IT, so I also got into coding that way. Game design just seemed like the right fit because I enjoy storytelling a lot and I love playing games. They’re a great thing to research because you just get to play video games. I felt like I had found the intersection between arts and STEM that I was looking for.

Taking Intro to Game Design my junior year was my first introduction to actual hands-on video game design. It’s a pretty sought-after class with only a few seats in there. But I was looking into it before then, since it seemed like the right way to go. On top of studio work, learning to code C# was a separate beast, but the course really helped me to grasp game design as a whole; and digital humanities as a label for what I was interested in.

2. How does playing the game work?

The user experience for Red Moss is like a visual novel, in a way. It’s not definitely not like a puzzle game, because I’m really interested in video games as storytelling. A big part of my practice is the humanities, talking about where I’m from. Coming from fine arts, that’s what we’re taught to do–to create our own voice. So it’s more like a point-and-click game where you explore the world, gather the story and then come to a resolution based on your own goals.

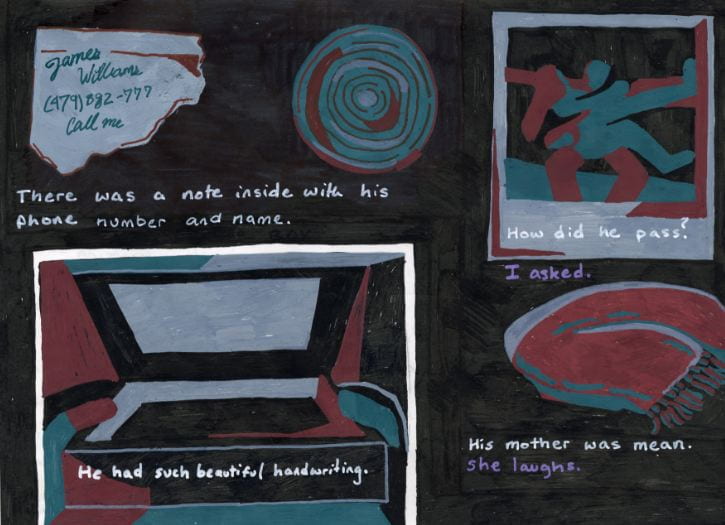

The story is coming from a similar place from where and how I grew up, though it’s also taking on different experiences from some of my friends. It puts the player into the spot of an 18-year-old just getting out of high school and living in an old, rundown fictional Arkansas town called Larking. Having players be in this abstract space puts them in the same spot as someone who’s never been to the South or who doesn’t understand fully what has happened here. The kid has lived there for a little while, but not long enough to kind of know what’s going on, and they come to experience the South in a separate way throughout the game. The basic narrative is trying to figure out what this character wants for their future by interacting with other people in the town. They learn whether or not they want to stay or leave Larking—that’s the final question that they must answer.

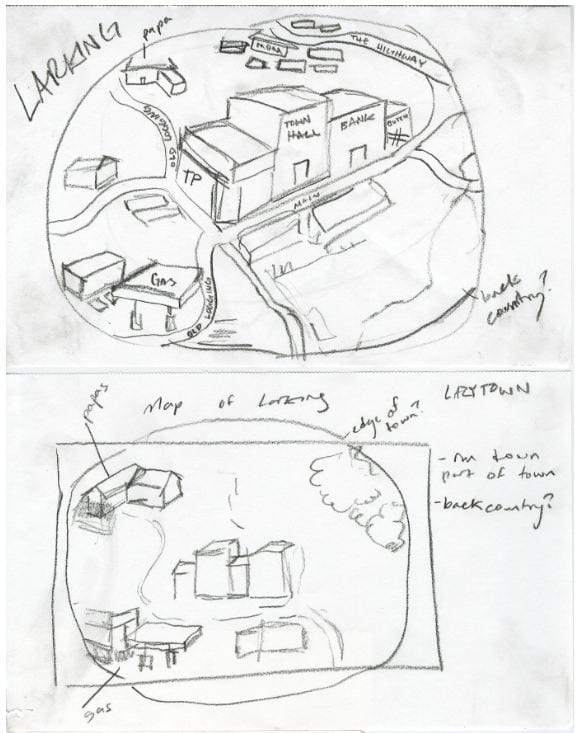

I grew up in Fayetteville, but also just drove around to research towns and did that kind of thing to create the game’s landscape. I also researched old postcard towns—places where the whole town almost completely fits on the back of a postcard. I started out by drawing Larking like that and thinking, where are the trailer homes going to be? Where’s downtown? Where’s the one gas station? Where’s the highway? Where does our main character live? Stuff like that. And so Red Moss is all really based around the environment of the town.

3. What does it mean to have a game that investigates the South to you?

I don’t think that there are a lot of mediums that can investigate the South this way, and this is the medium that I’m most interested in. It’s a way to just throw people into an experience—to have them see what it feels like and to have them interact with the space, and actually be in this space. Like any form of storytelling, you get to curate every single detail of what people are experiencing, down to how they interact with the space, even though it’s through the computer screen. For example, I could make this game look fully realistic, or I could make it the complete opposite. I get to decide that and that changes the audience’s perception of the world I’m creating.

In that way, it’s creating something about the contemporary South and I get to show them my version of it. One of the mantras of that I’ve been following as I make the game is, yeah, I get to show people my South, but I also get to reveal different things like nuances and different things that only people who live here know.

4. Is there specific research you’re doing alongside your own personal experience? Are there particular considerations you’ve kept in mind creating Red Moss?

Yeah, absolutely. I’m not a person of color, and I’m not someone who experiences a lot of prejudice in the South, though I do get some of that. But that’s just my own personal experience. And so I’m researching multiple sides of other people’s experiences of the South. And it can be hard to have a fully-rounded narrative with anything, so I’m definitely thinking about that. I’m reading a lot of Southern commentary and researching different writings about how people feel about the South and statistical data that’s about the South. I’m also talking to my friends as queer people in the south. Being queer is a big part of my life and so it’s made its way into the game.

I think that in a future version of the game I would really love to have more insight from other people, particularly people of color. Those experiences are a massive part of Southern culture and history and I don’t want to leave people out. And I also don’t feel like I’m the person to talk about it.

I’m interested to see what people say after playing the game, or what they feel about it. It’s coming from a place of growing up in the South and not wanting to stay here, and so I hope it maybe changes the perceptions of people who may have felt similarly to me as a kid. For other people, I’m just interested to see how they feel about it.

5. What do you see as the broader role of game design in education? What the digital humanities can offer students?

I think that the digital humanities has the potential to have a big place in curriculum and academics but that hasn’t been explored fully yet. Game design has been integrated into the curriculum at a lot of other colleges, though there are more opportunities to expand it here at the U of A. I would have loved to do more of that in my undergraduate career, and I would’ve majored in Game Design if I could’ve. I think game design’s one of the leading technological fields in terms of innovation and growth.

In terms of what I think it’s going to do, there’s so much value in creating 3D worlds and spaces. There’s a place for technology in the arts and for having science and the humanities interact, though I feel like there isn’t a place here yet. That’s kind of what my advisor, professor Fredrick, is fighting for: the interaction between digital and the humanities. It’s definitely a theory-based science and you can go anywhere with game design and the digital humanities. You can create virtual spaces to explore, but there’s also a lot of money to be made in advertising, architecture, things like that. The ability to try something out on your computer before actually bringing it into reality is a valuable tool that can be used across many disciplines.

In regards to my own education, this experience has made me want to go to grad school for game design. It’s also helped point me in the direction of what specific seat I want to hold in game design, because creating a game by yourself lets you experience everything. Funnily enough, it’s made me want to be a project manager for game design, because you’re the one in charge of the timeline, risk management and things like that.