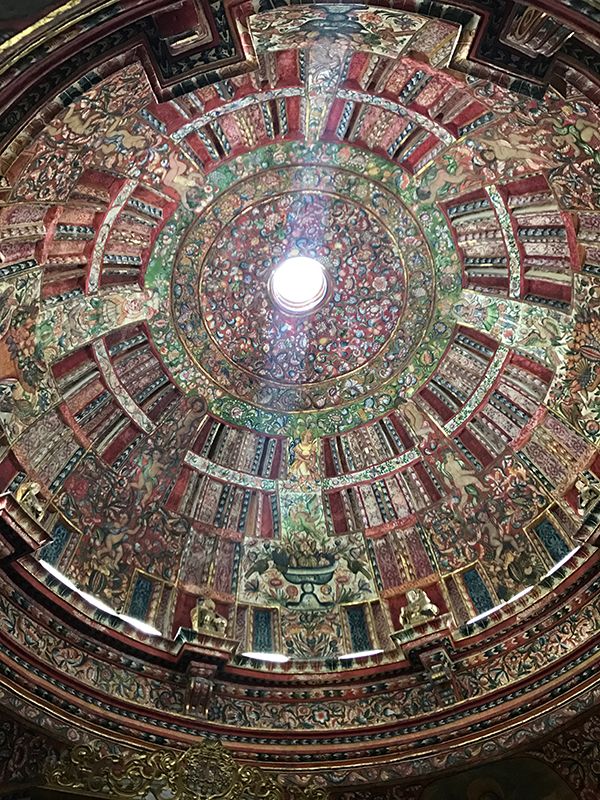

This beautiful dome crowns a jewel box chapel painted with flowers, birds, and patterns borrowed from Andean textiles.

The Spanish built their churches on the massive stone foundations of the Inca they conquered, but craftsmen took care to blend Andean and Incan themes into the usual Christian symbols. In this excerpt from her Peru journal, honors biology major Rashi Ghosh reflects on an especially beautiful example in Arequipa.

It was only the third day of the Peru study abroad trip, yet we were already on our second city—Arequipa. We had only landed in the beautiful white city just that afternoon, and the exploration of indigenous and colonial duality had already begun. After riding the bus into town, we stepped off and walked for a bit through the busy streets until we reached our first stop in Arequipa—La Compañía, a Jesuit complex. La Compañía presented a wide array of examples of the hybrid Baroque architectural style, with the integration of Andean style into Christian iconography contributing greatly to this fusion.

Just from standing outside the gate to the complex one could already see the Catholic colonialism and earthly Andean imagery blending together upon the face of the complex’s façade. On the outside of the cathedral, the intricate carvings and reliefs represented not only Christian symbols but Andean and even Incan ones as well. The numerous appearances of the Inca flower especially supported this. They appeared not only at the grand gateway to the cathedral, but on the columns and pillars in the courtyards as well.

The naturalization of Christian imagery also played a role in the hybrid Baroque style. Halos were transformed into seashells, and the many flower and vine carvings also added to the natural imagery of the cathedral. The door knockers on the large entrance doors took the form of lions—animals, which are quite classic subjects in Andean imagery, were transformed for a Christian purpose. Taking Catholic images and overlaying them with a more earthly feeling brought an Andean flair to the cathedral, reflecting the hybridity of the architecture.

Aside from the obvious display of duality of the grand façade, there were other marks of Andean and Baroque fusion found on other outer areas of the cathedral. Interestingly, carvings on the steps to one entrance were pointed out by our guide; these engravings appeared to be of temple-like steps and mountain scenery. This contributed a subtle undertone of Andean values to the cathedral from the very first steps into the complex. Although the exact intentions of these carvings are unknown, they appeared to be and could easily have been yet another integration of Andean qualities into Christian imagery.

The grand display of duality did not stop with the outside of La Compañía. Inside, the walls were covered in colorful patterns, reminiscent of Andean textile work. Even everyday Andean design was infused into the Baroque style, presenting a meaningful indigenous ambience within the walls of the Jesuit complex. In addition, there was a painting from the School of Cusco of the Virgin Mary depicted in a very geometrically triangular shape—like that of a mountain. This shape was especially symbolic as the Andeans worshipped the mountain Pachamama, the earth deity. By displaying this incorporation of an Andean deity into a Christian divinity, the Jesuits continued to promote a hybridity between their symbols and indigenous ones.

The duality of the two cultures were seen all throughout La Compañía, from the first steps into the cathedral to the very design of the walls. It was absolutely fascinating to see the two presented in harmony via the Andean hybrid Baroque style, creating a cultural fusion between the Jesuits and the indigenous peoples, all in an attempt to attract the natives to a new religious order and not make them feel out of place.

Walking away from La Compañía, I had to remind myself that it was only day three of the Peru exploration, and only day one in Arequipa, Peru’s second largest city. There would be more of these fascinating facades and fusions to uncover—this was indeed only a teaser to the journey ahead.