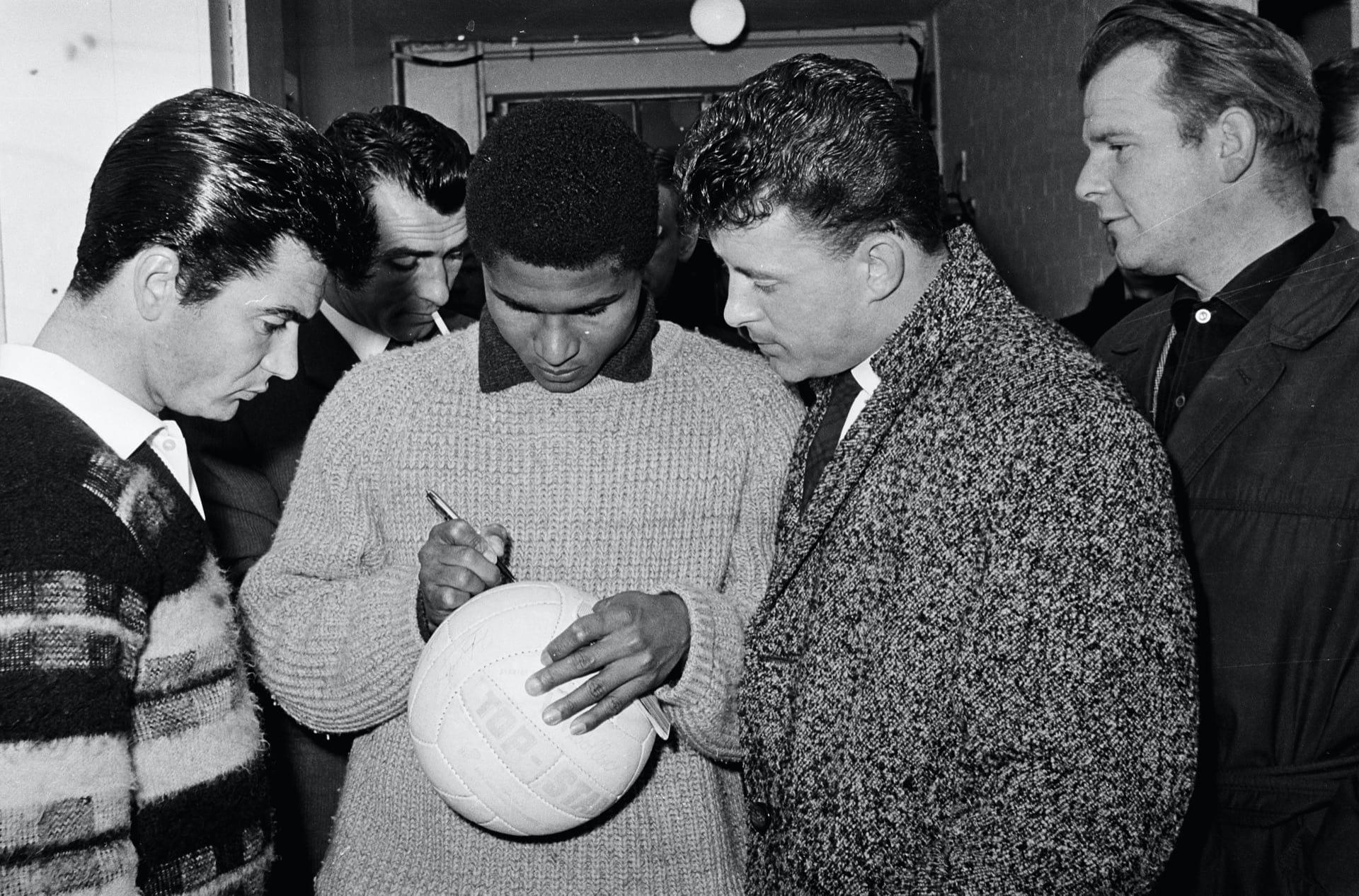

Eusébio (center left) signing a ball for Dutch midfielder Reinier Kreijermaat (center right) after a 1963 game between Benfica and Feyenoord.

by Todd Cleveland

In the summer of 2010, my wife, son (our younger son had yet to join us), and I moved to Lisbon, Portugal, for a series of months, so that I could continue work on a project that aimed to reconstruct the experiences and significance of an array of African soccer migrants who traveled from Portugal’s colonies on the continent to the metropole from the late 1940s until the mid-1970s. Eventually, this work was published as: Following the Ball: The Migration of African Soccer Players across the Portuguese Colonial Empire, 1949-1975 (Ohio University, 2017) and, subsequently, was translated into Portuguese: Seguindo a Bola: A Importância dos Futebolistas Africanos no Império Colonial Português (Lisbon, Portugal: Infinito Particular, 2022). During my time in Lisbon, I worked in the relevant archives and tracked down and interviewed dozens of these former players, many of whom had remained in Portugal following the conclusion of their playing careers. But there was one player who had remained elusive: Eusébio da Silva Ferreira. And, there were very good reasons for this.

Eusébio was born in the Portuguese colony of Mozambique in 1942 in the capital city, Lourenço Marques (now Maputo) to an African mother and a father of Portuguese descent. However, his father died when Eusébio was just 8 years old and he, thus, grew up impoverished. Even as his family struggled, the future soccer star was excelling on the pitch, joining Sporting Lourenço Marques (LM), the affiliate club of the powerhouse, Lisbon-based Sporting Clube de Portugal, at just 15 years of age in 1957. Typically, players who impressed at Sporting LM would “graduate” to the parent club in Lisbon. However, Benfica, Sporting’s crosstown rival “hijacked” the arrangements and whisked Eusébio away upon his much-heralded arrival in the metropole to check him into a modest hotel room in southern Portugal under an assumed name (“Ruth Malosso”) until things quieted down. Later, Eusébio’s mother would claim that her son rejected Sporting in favor of their crosstown rivals because: “Benfica gave big money.”

At Benfica, Eusébio flourished, playing for the club for 14 seasons and netting an astounding 317 goals during his career in the Portuguese capital. He also led Benfica to the 1962 European Cup title (the precursor to the UEFA Champions League) and helped the club reach the finals in 1963, 1965 and 1968. He also won the Ballon D’Or, soccer’s most prestigious individual award, and finished as runner-up for the commendation in 1962 and 1966. He even propelled Portugal’s national team to new heights, including a third-place finish in the 1966 FIFA World Cup. More than any other African- or Portuguese-born player, Eusébio elevated both club and country – Benfica and Portugal – to global footballing royalty and remains widely regarded as one of the top-15 players of all time.

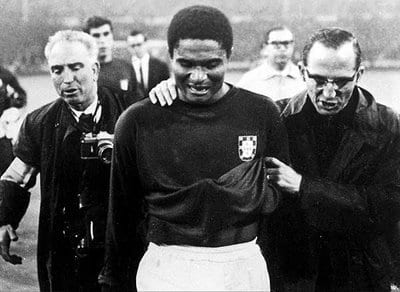

But Eusébio wasn’t Portuguese. Or was he? Although institutionalized racism prevailed throughout Portugal’s colonial empire, the country’s durable dictator, António Salazar, permitted the relocation of these highly capable soccer migrants to the metropole starting in the late 1940s and conferred upon them honorary Portuguese citizenship. Ever the diplomat, Eusébio consistently declared that he was both Mozambican and Portuguese in an attempt to remain apolitical, while repeatedly declaring that “soccer is my politics.” This neutrality gained further utility after the wars for independence broke out in Portugal’s African colonies: Angola in 1961, Guiné in 1963, and in Eusébio’s home colony/country of Mozambique the following year. These African soccer migrants were newly forced to negotiate the politically charged environment in the metropole while their African brothers were fighting – and dying – for freedom back home. Going forward, both the nationalist movements and the Portuguese regime attempted to use these footballers for propagandistic purposes, but most of them assumed the apolitical stance that Eusébio had adopted and kept their public comments limited to soccer and other innocuous topics, and thus weren’t particularly useful to either side during the conflicts.

Eusébio tearfully exiting the pitch after Portugal’s loss to England in the semifinals of the 1966 World Cup. At the time, Portugal was simultaneously waging a brutal counterinsurgency campaign against freedom fighters in his native Mozambique.

A largely bloodless coup in Portugal on April 25, 1974 – the Carnation Revolution – finally swept away the authoritarian regime. For the first time, these African soccer players could freely move abroad to ply their trade. In fact, Salazar had famously declared Eusébio a “national treasure” when his stellar play had sparked interest from a series of Italian clubs in the 1960s, which precluded any relocation further abroad. In the aftermath of the revolution, Eusébio relocated to North America, where he played for a series of forgettable clubs, including the Boston Minutemen, Monterrey, and Toronto Metros-Croatia. By then, injuries had robbed him of his former prowess, and over the five years after he left Benfica, which included stints back in Portugal and back again to the U.S., he netted a meager 30 goals in 93 appearances (compared with 317 goals in 301 appearances for Benfica).

Regardless, Eusébio had long since established himself as one of the greatest players of all time, which brings us to my interaction with the soccer legend. For months in the summer and into the fall of 2010, I tried to track Eusébio down. It wasn’t overly difficult to get his cell phone number. Portugal is a small, close-knit country, and everyone is seemingly only a few people removed from knowing just about anyone else in the country. But he didn’t always answer his phone and, at times, even when he did, he indicated that he was abroad (like so many other Lusophone African soccer migrants, he had elected to remain in Portugal following his playing days) and that I should call him back, usually in a couple of weeks once he returned home. Ok, fine. I’m a nobody – not even a journalist, eager to run (yet another) story on the legend. He was, at the time, working and traveling as a UEFA ambassador, traveling the world, comfortably nestled in one of those cushy jobs that you wish some entity had created for you. Regardless, I was growing desperate.

Thankfully, he finally agreed to meet me and sit down for an interview. Success! Right? Yes, but, I have to admit, even on the phone, I was nervous when speaking with him. He was always polite, but sometimes the connection was spotty, especially when he was overseas, and he’d grow a bit impatient. I had also been pestering him for some time at that point, and he only agreed to meet with me when I indicated that I’d be headed back to the U.S. shortly. I was running out of time. Previously, my research had been on diamond mine laborers in colonial Angola. So, I had interviewed scores of people, and in a foreign language, but none of those individuals, as remarkable and unyielding as they had been under extremely adverse conditions, were famous. Eusébio was.

Dutifully, I arrived early at the restaurant at which he indicated we should meet, even if Portugal isn’t exactly a place where punctuality is widely regarded. It was an odd time – 4:00 pm, if I remember correctly – as the Portuguese eat late lunches and even later dinners. Most restaurants are closed during the late afternoon. As I waited (and waited), I finally saw a black Mercedes sports car approach and determined this had to be him. I was right. But what I didn’t expect was that he did not bother to find a parking spot. He simply stopped near(ish) to the restaurant and parked his car in the middle of the street. I confess, this further intimated me. I mean, who does that? Movie stars? Other A-list celebrities? There was no valet service; that car stayed right where it was until he drove it away following our interview.

Some passers-by yelled “Boas tardes” (good afternoon) to Eusébio or simply hooted his name as he walked my way. As he got closer, I noticed that a part of his dress shirt was untucked and the front buttons were mismatched with the corresponding holes, such that his collar was higher on one side than the other. He looked as if he had thrown on some clothes following an all-night bender and hurried my way, just so he wouldn’t be too late. We subsequently made quick introductions, and he then ushered me inside the establishment. Gulp. Another wave of intimidation: the restaurant was a shrine to the soccer star. On virtually every inch of wall space, there were paintings, photos or newspaper clippings of the legend. I might as well have been sitting in his den.

It was at this moment of panic that he uttered the words that appear in the title of this post, “Gostaria de um pouco de cerveja e queijo?” (Would you like some beer and cheese?). But I was still mesmerized by my surroundings, including by the gentleman sitting across the table kindly asking if I was hungry or thirsty. Eusébio asked again and only then did I realize that he had been addressing me. But, this time, he didn’t wait for my response. He simply lifted his arm and yelled in the general direction of the kitchen, “Beer and cheese, please!” Although beer and cheese are popular in Portugal, they’re not generally a pairing, so the order struck me as a bit odd. But he was Eusébio, and he was seemingly in friendly confines. Moments later, the beverages and appetizer appeared. I’m convinced that the beer was intended as a “hair of the dog” for him, though there’s nothing in our ensuing conversation to suggest that he was struggling in any way. But, still, the sartorial mishaps continued to feature in my mind.

Just after our first sips of beer and nibbles of cheese, the soccer star abruptly inquired, “How long is this going to take?” I feebly responded, “Maybe about an hour?” To which he replied, “Ou menos” (Or less). I was stunned: all this time to finally interview the soccer legend, and we were poised to race through a conversation, intermittently interrupted by the consumption of beer and cheese? Oh well, we were in Eusébio’s palace, so I thought to myself, let’s just make the best of it and see how it goes.

Based on what I’ve shared heretofore, you wouldn’t be wrong to suspect that the interview wasn’t ultimately very long or very useful to my research. Yet, there was clearly something magical about the beer and cheese. Eusébio quickly discovered that I wasn’t going to ask him about his toughest opponent, his favorite victory or his bitterest defeat. Rather, as a social historian, I wanted to know what these migrant laborers – as I consider them in my book – did before and after they left the pitch. How did they navigate Portuguese society as members of a minute racial minority in the metropole, especially after young Portuguese conscripts started returning home in body bags or with missing limbs owing to the insurgencies in the colonies? What did he and his teammates do recreationally, during the week, as they prepared for games on the weekends? What did they miss the most from Mozambique, Angola, Cape Verde or the other Portuguese colonies in Africa? At one point, incredulous, Eusébio paused and declared that no one had ever asked him about these things. He further indicated that my queries had prompted him to think about things he hadn’t revisited for decades. I watched him intently as he replayed those fond memories in his head.

Some two hours later, after we had consumed ample beer and cheese (refills on both were just a quick shout away), we remained the only non-staff in the establishment. I had exhausted my questioning, and it seemed like an ideal time to conclude. We shared a series of genuine “muitos obrigados” (thank you very much) and a hug, and we departed together. There was no bill to be paid.

As he drove away, I stood, fixated on the sidewalk outside the restaurant, just staring until the Mercedes vanished from sight. My next thought was that I couldn’t wait to get home to share with my wife everything that had just transpired (our son was only two at the time, so I continue to forgive him for his indifference regarding the whole matter). She knew how much this prospect had meant to me, but in practice, it meant a whole lot more. I wasn’t sure how the interview would go – I’d read countless interviews he’d given previously, often reciting the same stock answers. But ours went in a direction that I hadn’t quite anticipated, and to which Eusébio certainly hadn’t anticipated. In some regards, it felt as if we had both done each other a favor. For me, his testimony was extremely insightful and features prominently in my book on him and his footballing peers. For Eusébio, I suspect that in his overly busy world, always pressed and reminded about his on-the-pitch achievements and moments, he wasn’t inclined to remember all the wonderful (and challenging) experiences he had away from the pitch in his younger years as often as maybe he would have liked? Who knows, maybe he was actually put out with me – an ambitious, pestering, early career professor – and simply used the beer and cheese to pass the time while I continued to probe his time in metropolitan Portugal, a bygone era? But that’s not how I choose to remember it. And I don’t think the soccer great did either.

* * *

Almost a decade ago, in 2014, at the age of 71, Eusébio passed away. Outside Benfica’s stadium, in the days immediately following his death, the statue of him became an impromptu shrine. People came and sang, and they cried. The government declared three days of national mourning. The soccer legend was eventually laid to rest in Portugal’s National Pantheon.

I’ve told this story many times, though I’d never put it in writing. So, I’m grateful that “The Beautiful Game on the Hill” has prompted me to sit down, type it out and engage my own fond memories of my interaction with Eusébio. I’ve met very few celebrities in my life, but I’m pretty sure that not all of them would have so generously donated their time to and shared such intimate details of their lives with someone they barely knew and who didn’t possess much in the way of credentials. I’ll always remain grateful for Eusébio’s multiple generosities toward me and toward so many other people in so many other different, though similarly meaningful, ways. With these myriad contributions in mind, it seems just about right, if wholly incommensurate, that Eusébio didn’t get billed for the beer and cheese. Rest In Peace, Senhor.

Todd Cleveland is a professor in the Department of History, where he teaches classes on African and Sports History, including one (admittedly uncreatively titled) course that combines those two areas of interest: “History of Sports in Africa” (see, I told you it was uncreatively titled). His passion for soccer began while playing during high school (albeit as a back-up striker with limited goal-scoring abilities), watching those atrocious MISL games, and eventually living in London, where he discovered and subsequently fell in love with Arsenal Football Club. He has now been a long-suffering Arsenal fan for over thirty years, patiently awaiting a return to the glory years of “The Invincibles,” Arsenal’s undefeated 2003-2004 squad. Along the way, he has published Following the Ball: The Migration of African Soccer Players across the Portuguese Colonial Empire, 1949-1975 (Ohio University Press, 2017), as well as a series of soccer-related articles, but readily admits that his own writing pales in comparison to his favorite soccer author, Eduardo Galeano. His favorite soccer quote comes from Arsenal legend, Tony Adams: “Play for the name on the front of the shirt, and they’ll remember the name on the back.” If only we all wore jerseys.