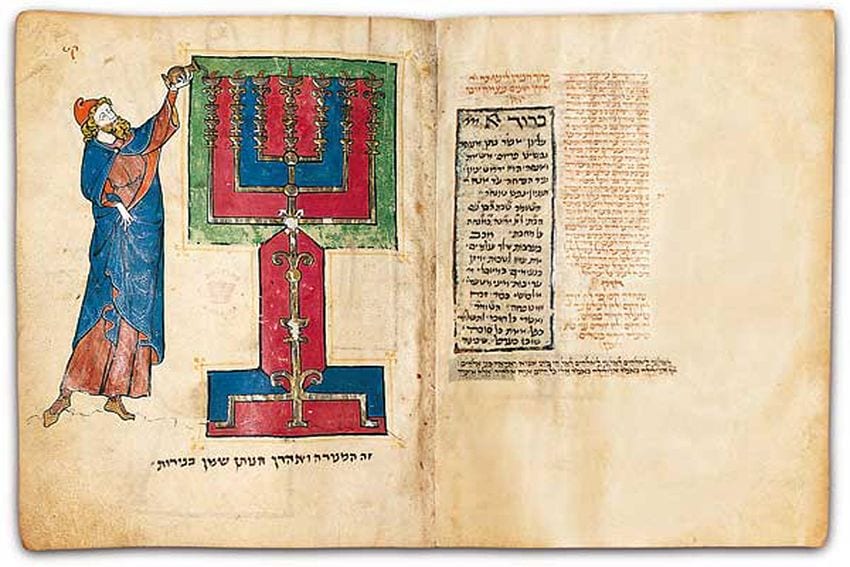

In this 13th c. manuscript folio from Leviticus, Aaron pours oil into the lighted lamps of the Tabernacle menorah, the seven-branched candelabrum. English: Folios 113b-114a of the North French Hebrew Miscellany manuscript. Binyamin 392 North French Hebrew Miscellany folio 5B.l – Alamy; Image ID: MYN2C3.

Elizabeth Cooper is an honors history and anthropology major with an archaeology concentration. Currently she is participating in the Retro Reading course “Bible,” led by Honors College Dean Lynda Coon, a medieval historian by trade. In this post, Elizabeth considers the theme of “purity” in the book of Leviticus and the ways in which this theme has been interpreted, and misinterpreted, over time.

Due to its frequent use as a source for controversial religious views on a variety of topics ranging from homosexuality to ritual taboo, Leviticus is certainly not the most popular book of either the Tanakh or the Christian Bible. However, this unpopularity and contentious nature makes the text no less valuable in terms of its addition to and enrichment of biblical scholarship. Leviticus is a textual gold mine of theological imagery, ritual logic, and religious symbolism that has resulted in numerous interpretations of this crucial text over the centuries since its beginnings in the 6th century BCE. While temporal and spatial separation from the initial Israelite audience can make studying the text difficult, careful analysis and study of Leviticus’s historical context has revealed key themes and components that help to explain the sometimes-elusive meaning of the text. Understanding this background also helps scholars and readers to avoid taking phrases from Leviticus out of context, such as the oft-cited commandment regarding a man laying with another man.

One theme that can be read explicitly and implicitly throughout the text and has been heavily debated by scholars is that of purity. According to modern Jewish scholars, the goal of the content of Leviticus (mainly laws and commandments concerning purification and atonement for sin) is to provide instruction for the Israelite people to fulfill their purpose of sanctifying the name of God. This purpose is accomplished by each person and by the community as a whole maintaining a purity of the body and the Tabernacle sanctuary, which can be tarnished through physical contact with impure objects, people, or animals. Leviticus details various rituals and commandments in order to preserve this physical purity, including offering sacrifices to atone for and remove sin or impurity, avoiding contact with things that are considered unclean, and abstaining from eating animals that are considered “abominations.”

While the rationale behind these “abominations” of the animal kingdom can be difficult for modern readers to understand, there have been many purity-centric interpretations of the reasoning behind the text’s designation of some animals as unclean “abominations” and others as clean and acceptable for the Israelites to eat. Mary Douglas, a scholar of the anthropology of religion, suggests that these designations relate to the ability of an animal to fit into one of the three areas in which it was designed to live in during the creation sequence in Genesis—either in the sky, in the water, or on the land. Each of these classes has specific characteristics that an animal must meet in order to be considered clean or pure, and thus available for the Israelites to eat. For example, Leviticus 11.2-8 details the requirements for land animals as both chewing cud and having true cloven hoofs (typical characteristics of land animals like cattle and livestock). This excludes from consumption animals that do not have these characteristics, such as hare and pigs. The ability of an animal to fit into this classification reinforces the central theme of purity in Leviticus as only animals that conform to the purity of their original creation classification can be consumed, and those which do not conform cause impurity in the consumer.

Another interpretation of the theme of purity in Leviticus suggests that the rituals and instructions detailed in the text are the results of efforts by early Jewish priests to combat the prevalent beliefs and ideas of contemporary Mesopotamian “pagan” religions, such as those of the Assyrians. According to Jacob Milgrom’s commentary on Leviticus, one of the central principles of these pagan religions is the belief in a “metadivine realm” in which deities and many lesser entities, both malicious and friendly, exist alongside humans. The malicious entities, or demons, are thought in pagan religions to be the source of bodily impurity. To counter this, Milgrom suggests that early Israelite prohibitions and commandments concerning impure things, such as those found in Leviticus, imply that impurity is the result of the physical world (i.e. an impure object, animal, or person) rather than a demonic force of the “metadivine” world. Examples of this association of impurity with the physical world are scattered throughout Leviticus, but the theme is particularly noticeable in passages such as those concerning the contamination of an “affected” cloth, the uncleanliness of an animal carcass, and the impurity of the bedding of a menstruating woman. This campaign against the ideas of pagan religions bolsters the ideals of purity in the religious practices of the Israelites, and reflects an attempt to maintain the purity of the practices themselves amongst the many outside influences present in the Mesopotamian region.

For further reading:

“Leviticus” in eds. Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, The Jewish Study Bible (Oxford, 1985), 203-280.

Mary Douglas, “The Abominations of Leviticus,” in her Purity and Danger: An Analysis of the Concepts of Pollution and Taboo (London, 1966), 41-57.

Jacob Milgrom, “Priestly Theology,” and “The Priest,” in Jacob Milgrom, trans., The Anchor Bible: Leviticus 1-16 (New York, 1991), 42-51, and 52-57.