[imagebrowser id=15]

Tyler Johnson, a senior history/classical studies major at the UA, is near the completion of his honors thesis – the virtual reconstruction of the house of Octavius Quartio in Pompeii. Tyler visited Pompeii in late January and has spent more than 200 hours in the computer lab modeling the house. His model will be completed in early July and the entire project can be viewed at the Digital Pompeii classroom website. Tyler hopes to earn a doctoral degree in archaeology and teach at a university.

I am a senior in the Fulbright College who received an Honors College Research Grant to fund research for my honors thesis on virtually reconstructing Pompeian houses. As a history/classical studies student, I chose a topic for my thesis that not only applies to both of these fields, but encompasses skills relating to computer science, graphic design, and archaeology. My project explores the use of 3D modeling software and game engine technology in reproducing and analyzing the remains of art and space in Pompeii, the ancient Roman city that was buried and preserved by the 79 CE eruption of Mt. Vesuvius. The firestorm of falling pumice and ash entombed the cities and villas that dotted the area, maintaining with pristine quality the most fundamental physical remains of society in the Roman-era Bay of Naples: structures both domestic and public, high traffic thoroughways and narrow alleys, artifacts of every sort, grand frescoes and lowbrow graffiti, and even the very bones of the victims of the disaster.

Despite the apparent abundance of evidence – or perhaps precisely because of it – as modern viewers we continue to search for the best interpretive tools for understanding houses and social life in Pompeii. Decoration and space in Pompeian houses seem to have functioned holistically, with each part responding to the other to create an ensemble. Given the inaccurate methods of early excavators, the removal of many frescoes from their original location, and a poor history of preservation at the site, this ensemble effect can no longer be experienced for most houses. This confounds the interpretive challenge at Pompeii and creates a need for a research approach that provides virtual recreations of “living” Pompeian environments – including immersive elements such as lighting, audio, water features, and gardens – and a reunification of the decorative sequences within and between Pompeian houses.

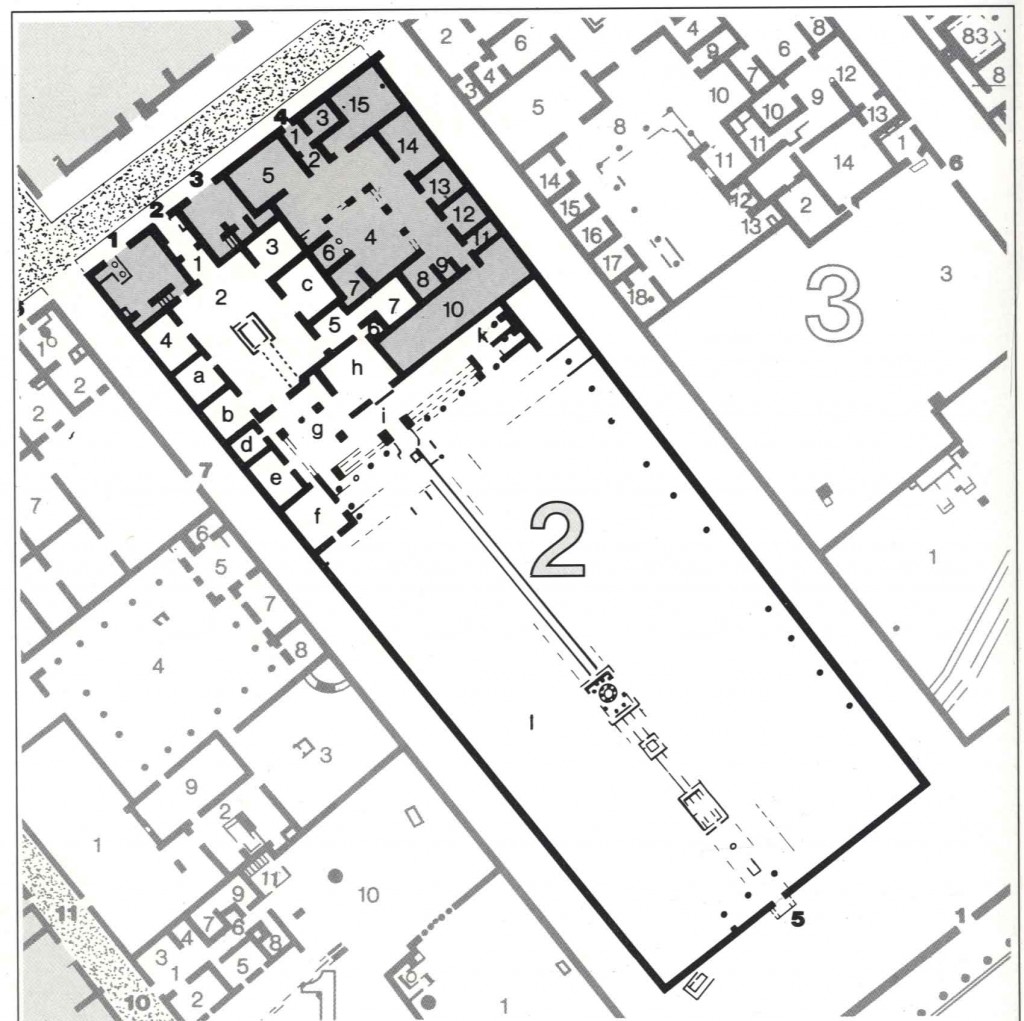

To respond to this challenge, I have chosen to use the Unity game engine to recreate one house in Pompeii, the extensively decorated Casa di Octavius Quartio. While Roman homes can no longer be experienced like they once were, Unity provides for the construction of a versatile environment that can be adjusted in terms of lighting, the placement of floral decoration, and ambient sound, among other things. This model, combined with methods of analyzing view sheds and room sequences, allows me to consider how the art and space of the house function to convey social messages intended for Roman viewers. For instance, what artistic themes signify socially central rooms? How does door height correspond to placement within the house? Answering these questions is the first step to elucidating the social function of Roman homes.

The funding I received from the Honors College was used entirely to fund a trip to Pompeii at the end of January 2012. For this trip, I planned to spend several hours on site at the Casa di Octavius Quartio. During this time, I would photograph each bit of space within the house, including the elaborate frescoes and color samples thatwould be used as textures for my model. I would also obtain accurate measurements of all the house’s dimensions, since such data is not published. In addition to time on site, I also obtained permission to photograph the statuary that was found in the house.

Unfortunately, due to an Italian bureaucratic obstacle, I was not able to enter the Casa di Octavius Quartio once I reached Pompeii. A free–standing pilaster in the garden area had partially crumbled, and due to a decree of the local magistrate, the building could not be entered until it was inspected. Nevertheless, I was able to take measurements and photos from outside, which has proved helpful in deducing the dimensions of the rest of the house. Also, the two storefronts that are connected to the property were not barricaded, so I was able to measure and photograph these spaces. Luckily, my experience in the Pompeii storerooms was successful. I was able to photograph several of the house’s statuary, and the data from these images can be used to create 3D models of the artifacts.

Although my research period for this grant ended in late April, I will actually continue the project until the end of June (my graduation date has since been extended to this time). Nevertheless, I have already spent over 200 hours in Dr. Dave Fredrick’s computer lab, working on modeling the house, arranging the textures of its surfaces, and using network analysis programs to obtain mathematical data about the quality of its spaces. Despite the setbacks, my trip to Pompeii was extremely informative both concerning the house itself and Pompeii as a whole. These findings are being used to supplement my findings. Although my conclusions are not solidified, I am currently nearing completion and have built a strong analysis of the house’s spatial and artistic character. Especially, I have learned that the house’s rooms form definite subsets of spatial types that share levels of decoration and social function. I have also found that the traditional descriptions of the room types within the house (dining, bedroom, etc) are entirely unfounded based on the artistic and artifact record. Unfortunately, the evidence for the house has proven to be poorly documented, unorganized, incomplete, and spread out over a variety of sources. Little has been said about the house that can be definitely ascertained. I hope for my project to form the first step of truly understanding the site in spatial and artistic terms.

My faculty mentor, David Fredrick, has played an irreplaceable role in this project. He has been present in the lab for many hours of my work, and his knowledge of Pompeii and 3D modeling informs the basis of my methodology. I have greatly enjoyed this project. I will continue similar research in graduate school, here at the Arkansas’s comparative literature program. I plan to obtain a doctoral degree eventually, and become a professor of archaeology or classical history.