In 2019 landscape architecture major Beau Burris extended his semester in Rome by traveling throughout Western Europe to experience more examples of design on steroids — vast spaces designed to impress. The trip was eye-opening and a good preparation for Beau’s honors thesis, which compared Louis XIV’s Versailles to our own national site populated by “god-heroes” – Washington, D.C.

My name is Beau Burris. My research is about design as power in public spaces, and I’m looking at the Palace of Versailles and Washington, D.C. in a comparative case study. I’m majoring in landscape architecture, which means I’ll be actively shaping public space and affecting the way people live their everyday lives; this research is intended to help me understand how to do that in an effective, benevolent way.

On this trip, I sketched and photographed my way through Milan, Geneva, Paris, Versailles and London. Design research is a lot less straightforward than in more pragmatic research fields, so my trip was mostly about observing and engaging the spaces I visited through drawing and photography. I asked questions like “how does this place feel? How do people use it? How does the architecture interact with the landscape? How does sculpture and figural iconography affect the space?” What I found will be profoundly impactful in honing my capstone. I’ve researched and found images of the types of places I’ve studied—I’ve just visited them and seen them in action—now I get to double down on the written research and fill in the gaps.

Milan and Geneva were one-night stops along the way to Paris. In Milan, I looked at the Milan Cathedral as a center of power, noting that the city grew up around it in a series of great ripples. It was the absolute heart of the city, and it was bedecked in the stunning lacework of gothic-carved marble; it was at a massive scale. The way it dominated the Piazza del Duomo said volumes about the power of the Catholic Church and of Milan as a city. Geneva is a smaller city, much more subtle in its cues on power. In Geneva, the power is in the small scale. The city hugs lake Geneva and straddles the Rhône—it doesn’t dominate the land as the grand axes at Versailles do. But the richness and detail of the architecture, the sparkling clean, carefully-paved streets and premium materials point to the city’s renowned wealth.

Paris and Versailles were, admittedly, predictable in their displays of power through design. (Although I’m sure it depends on who you ask—I’ve done too much reading on them both for much to surprise me.) During my one day in Paris, I focused on the Louvre and the Tuileries Gardens, as Louis XIV lived there before moving the court to Versailles. His landscape designer, Andre Le Notre, also had a hand in laying out the gardens long before becoming a master of the French Formal style. The key to Versailles and the Louvre is sequence, structure, and scale. There is a particular, ritual approach to the palaces, a sequence where everything fades away but the paving underfoot and the looming façades ahead. There is strict symmetry and rhythm to the façades themselves and to the landscape which spreads out in front of them—an easily legible structure. Their scale is massive and hard to reconcile with the human body. These all combine to create a feeling of power.

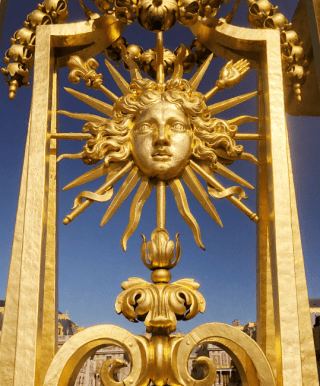

Versailles takes it up a notch, though. It introduces joy. At the intersection of great colliding axes, everything is visible: dancing water, playful statues, and terraces of orange trees and brilliant flowers bring the place to life. There are serious undertones, no doubt, and the seal of the Sun King is an ever-present reminder that it is by his will that you are enjoying yourself, but it’s a magical place nonetheless. This, too, is power—the ability not just to create imposing space, but to create places that inspire joy and wonder. Louis XIV was a great lover of the performing arts—he was a fantastic dancer and often played parts in ballets for the court’s entertainment. There are motives of power there, but especially after visiting Versailles, I’m convinced he was just as interested in fun. Versailles was his stage set, and he was putting on one impressive show.

My final day was in London. I quickly realized that Buckingham Palace could be a thesis on design as power on its own. It has all the richness and history of Versailles, but with one profound difference: it is still the resident of a monarch. Now, the British royal family functions a lot differently than the court of Versailles once did, but it’s so interesting to see these little iconographic power moves going in—I saw multiple plaques on sculptures and monuments commemorating Queen Elizabeth II’s Golden and Diamond Jubilees. Similar to Versailles, grand axes extend out from the palace into the city; it’s a stage set. At the intersection of these axes stands the Victoria Memorial—a glittering, massive sculpture dedicated to the life of Queen Victoria.

In retrospect, I realize that there is no possible way my capstone project could be sound and well-rounded without visiting these places of power in person. I understand them now in a way that goes beyond what I can read in journals and see in photographs—I have touched them and experienced them as real people do. I’ve watched these real people — how they respond to certain spaces, what excites them, what they photograph. That’s knowledge. That’s power. I’m looking forward to diving head-first back into scholarly research, using all of this profound new information to craft a capstone worthy of the places that inspire it.